It took several drafts to get the letters right. To capture her boy who, just a few short months before, had been so full of life, energy, and love. To distill him into the two dimensionality of words on paper.

Three weeks earlier, the thread that held Christine Cheers’s world together had been ripped clean away, sending her whole life spinning like an off-balance top. On Wednesday, February 21, 2018, someone on the other end of the phone had said the words that bring any parent to their knees: “There’s been an accident.”

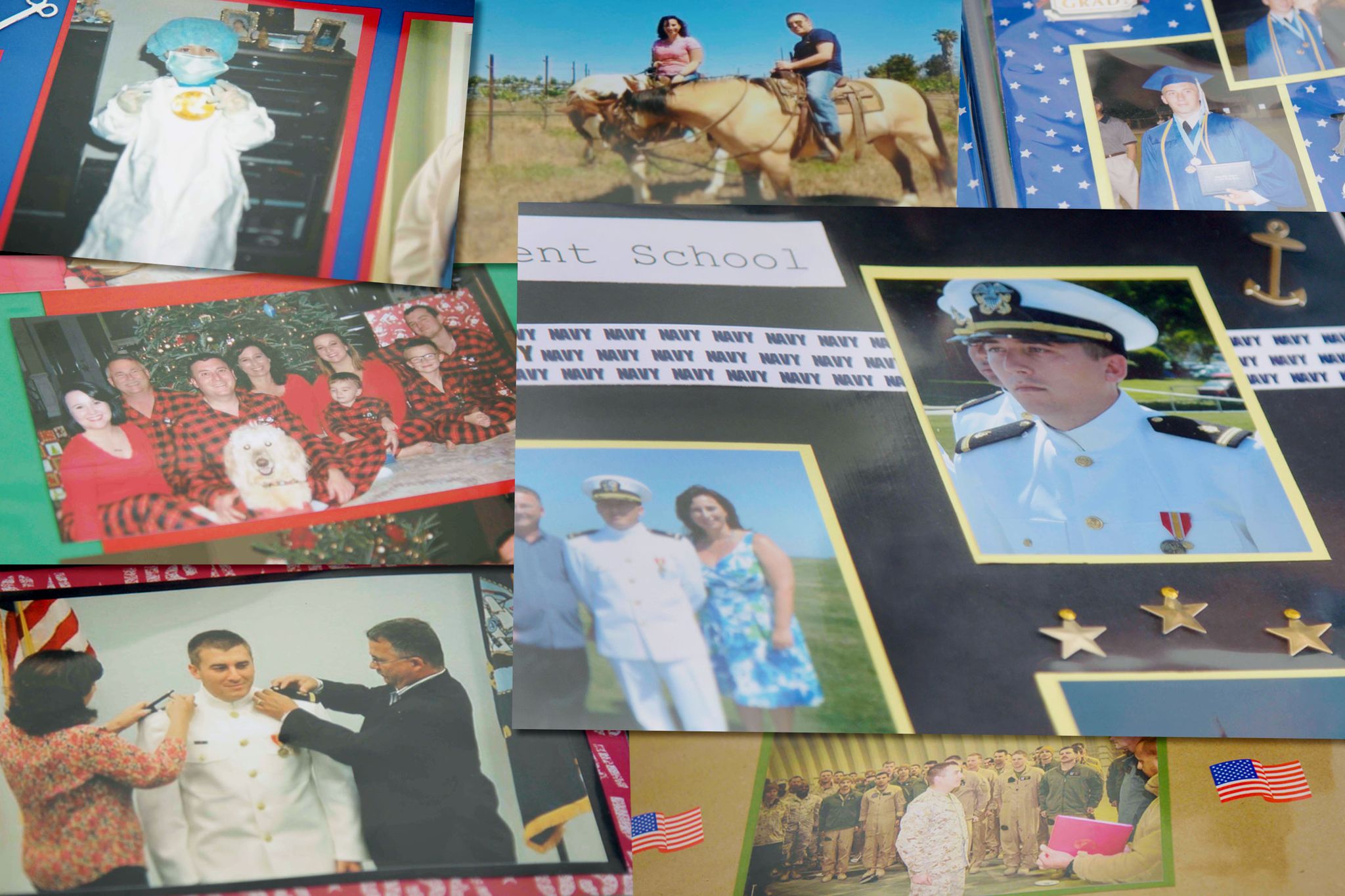

Her son, 32-year-old Navy flight surgeon James Mazzuchelli had been injured in a helicopter training mission at Camp Pendleton. If she wanted to see him while he was still alive, she needed to get on the next flight from Jacksonville, Florida, to San Diego—and she needed to pray.

James was still breathing when Christine and her husband, David, arrived at Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, California, the next morning. But it soon became clear that his condition would not improve. Machines were keeping him alive, and the doctors told Christine that what she was seeing was likely his future—that her scuba-diving, world-traveling, over-achiever of a son was never going to wake up.

There in the sterile hospital room, Christine flashed back to James as a teenager, coming home from school and making a proclamation that surprised her. As he and his friends worked toward their learner’s permits, they’d sat through a presentation on organ donation. James walked in the door and told his mother frankly that he wished to be an organ donor. “It was kind of unusual for a kid that age,” she remembers.

Under the fluorescent lights, with the rhythmic beeping of life-sustaining machines punctuating the silence, it was time for Christine to finish what James had started on that day 17 years before. It was time to honor the spirit of a man who had switched his major from commerce engineering to pre-med because he wanted to help people. It was time to make her very worst day some stranger’s best one.

Christine instructed the hospital to begin the organ donation process. She knew those few words, as hard as they were to say, were the right ones. What she did not yet know was the way those heavy words would ripple outward like a stone dropping into a still pond: allowing a man to return to work, a veteran to get his health back, and an ailing cyclist to get back on his bike. And how those little waves would slowly smooth out the edges of her own grief.

Mike Cohen was in trouble. It was day one of his 1,426-mile ride across the United States, and his heart was not cooperating. They’d gotten a late start out of San Diego. Perhaps he had not eaten enough or hydrated properly, or maybe it was a lack of rest—the past few days had been packed with trip preparations. Whatever the cause, it didn’t really matter. What mattered was that he had to keep his heart rate under 150 beats per minute, and the steep Cuyamaca Mountains east of San Diego were sending it sky high. The sun was setting, and he would soon be pedaling in the dark. But he had to take it easier: doctor’s orders.

His friend Seton Edgerton rode alongside him. They had rigged up Mike’s heart rate monitor so Edgerton could see it on his computer, and he watched the screen, helpless, as his friend’s heart refused to cooperate.

Mike had done a cross-county bike ride once before, back in 2012. This time was different. He was different. His body had been through so much since then. Both men were thinking to themselves: This is just day one. Should we even be attempting this? Neither dared to ask the question out loud.

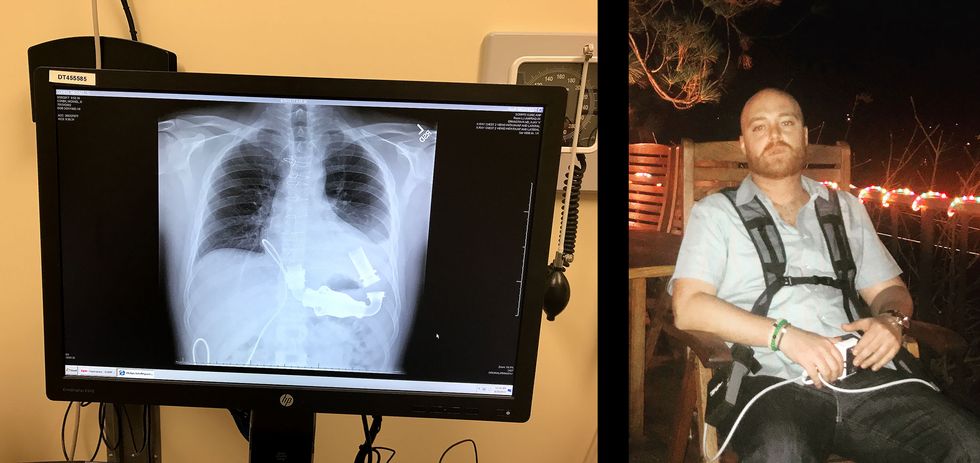

Eighteen months earlier, on February 24, 2018, Mike Cohen was in the Sulpizio Cardiovascular Center at UC San Diego Health waiting for a new heart. Heart transplant priority lists are tricky. You have to be sick enough to truly need the new organ, but not so sick you can’t withstand the 12-hour surgery, says Anuj Shah, MD, an interventional cardiologist based in New Jersey. Mike fit those parameters. With an active clot and a left ventricular assistance device (or LVAD) literally pumping blood that his heart was too weak to move, he’d been at the top of the list for a month.

He’d turned 33 three days before, and as he blew out the candles, he wished for a new heart. Today, blood work showed the clot had dissolved enough that he could safely go home, but he probably wasn’t going to get a new heart any time soon. Another tricky thing about the transplant list—you get a month at the top. Tomorrow he’d be kicked to the bottom.

Mike was just 18 when he’d been diagnosed with an aggressive form of leukemia in 2004. Doctors warned him that the treatment protocol could cause lasting damage to his heart. At the time, surviving cancer seemed like the more pressing concern. He took his treatment seriously, doing the radiation and chemo, and even moving from New York to San Diego for his last year of chemo because his oncologist felt mild weather would be easier on his body. The risk had paid off—two years after his diagnosis, he was cancer-free. And the move had been a good fit too. As soon as he was healthy enough to get outside, he was hiking in the nearby hills or riding his bike. A casual cyclist as a kid, Mike became bike-obsessed as a young adult, upgrading from a hybrid to a road bike, then adding a mountain bike to his collection.

To celebrate his sixth year without cancer, Mike decided to ride his bike from the hospital in San Diego where physicians had pronounced him cancer-free, to the hospital in Long Island, New York, where doctors had delivered his diagnosis. Like most grand adventures, the cross-country ride plan was hatched after a few drinks at his local bar. And like many alcohol-inspired adventures, it was kind of a disaster. Every day was a grind. Somewhere in eastern Arizona, Mike was so over it he nearly threw his bike into oncoming traffic. And between Kansas and the Eastern seaboard, his relationship with the friend accompanying him soured.

What Mike didn’t know during that ride was that his heart was beginning to fail; and in the years that followed, his health continued to deteriorate. Even on days he didn’t ride his bike, he always felt tired and could not make it through the day without a nap. One evening in 2017, he started having chest pains. “At first I thought it was indigestion,” he says. (He’d just eaten a steak.) Then he felt a pain in his jaw and a shooting pain in his left arm. “I took an inventory in my head and I was like, I don’t recognize these feelings.” He texted his brother: Get here now. I think I have to go to the hospital. He didn’t dare put in the message that he thought he was having a heart attack. “Who texts that?” he says.

At the hospital, tests confirmed that a golf-ball-sized clot had lodged in his left ventricle. They tried blood thinners, but the clot wouldn’t budge. Soon hospital staff was preparing him for open-heart surgery to install the LVAD, which would do the pumping that his heart—now blocked by a clot—couldn’t accomplish. The doctors told him the device could work for eight months or eight years. Six months later, though, he was back in the hospital with another clot. His heart was failing.

Mike’s old life—where he rode his bike across the country and hiked and biked all over San Diego—seemed like a thousand lifetimes ago. His implanted LVAD required constant access to an electrical outlet, which meant Mike was literally tethered to the indoors by a cord that ran out of his abdomen. Even with an emergency backup battery pack, “You couldn’t go out in public because you couldn’t trust that someone wouldn’t knock into the cord,” he says. “I couldn’t even shower.” He sold his bikes, including the nearly new Trek Stache 9.6 he’d ridden precisely five times before his heart attack. It hurt to send them to a new home, but it hurt more to be reminded that he might never ride again.

In the cardiac unit on February 24, 2018, as Mike waited for his discharge papers, he walked a lap around the hospital floor, then packed his bag to go home. A nurse walked in. “I have good news, and I have bad news,” she said. Mike asked for the bad news first.

The nurse announced that he wouldn’t be going home that day after all. The good news? They’d found him a heart.

Mike knew better than to get his hopes up. Twice before, hospital staff thought they had a heart for him. But then the size wasn’t quite right, or the organ wasn’t healthy enough. Day stretched into evening. The signs started to look promising—no one had come to tell him it wasn’t going to happen. Nurses double-checked his height and weight and got his vitals one more time.

A little before midnight, hospital staff wheeled Mike to an elevator. It was happening. He was more excited than nervous, ready to move on from the chapter of his life where he lived in a hospital full time. There was a chance that he’d never wake up, he knew that. But the chance of waking up with a healthy heart far outweighed it. “There’s a photo of me hugging my girlfriend and crying in her arms. It was like, we’re finally there. Maybe this is the end. Maybe it’s the beginning,” he says.

Christine Cheers wasn’t going home until every last one of James’s organs left the building.

She and David watched hospital employees carry coolers from the operating room: his left kidney and pancreas en route to a man in San Diego; his right kidney to a veteran at Walter Reed Medical Center. Next James’s liver headed to the Bay Area. His corneas went to the San Diego eye bank. Tissue and bone also went to nearby tissue and bone banks. All that was left was his heart.

“That was the one I cared about most,” Christine says. James was more than just her beloved boy; as a soldier and physician, he embodied the ideals of bravery and altruism. “James had such an amazing heart,” she says.

With organ donor surgeries, time is critical; organs must be harvested and transported within hours to stay viable, and transplant surgeons move efficiently. Interactions with the donor family can complicate things, and the person charged with transporting James’s heart had only a few hours to get the precious cargo to its new home. He picked up his cooler and headed toward a rear exit so he wouldn’t pass the family.

When a hospital representative delivered the news that James’s heart had already gone, David Cheers felt a flash of anger. This was the one thing his bereft wife had asked for; the one thing. He ran into the hallway. He could see the image of someone holding a cooler reflected in a curved safety mirror. The person transporting James’s heart had gotten turned around in the maze of hospital corridors and couldn’t find his way out. Now he was backtracking. David yelled for Christine. The pair watched through the mirror as James’s heart left the building.

On February 25, 2018, Mike Cohen woke up in a hospital bed with a breathing tube in his mouth and James Mazzuchelli’s heart beating in his chest.

A heart transplant is a major surgery, and Mike was prepared for an arduous recovery. He’d been sick for so long. First with cancer, then with a faulty heart. He’d spent nearly his entire young adulthood focusing on his health.

This time, his energy seemed to improve immediately: He took his first steps around his hospital room just five days later and was walking the hallways shortly after. “The old heart was like a two. With the LVAD my energy went to like four to five,” he says. “This heart is a 10.”

After a little more than two weeks, he was sent home with instructions to report to cardiac rehab, where, for the first few days, he was limited to slow walking on a treadmill. Across the room from the treadmill, he spied a stationary bike. He knew he wasn’t ready yet, but it became a beacon. And two weeks later, with his doctor’s okay, he finally threw a leg over and soft-pedaled.

From there, it wasn’t long before he started thinking bigger. He itched to get back on a bike outside. The new heart felt so dramatically different that he even dared to imagine whether another cross-country ride might be possible.

In the weeks after James’s death, Christine Cheers descended into a grief so deep that climbing out seemed impossible. She found herself needing to know that James’s organs had helped people. That the recipients were doing alright.

The one part of the letter that Christine wanted to get right was the part about what organ donation had meant to her son. How glad he would be that his heart and kidneys and tissue were helping someone else. She didn’t want the recipients to feel guilty about the heft and gravitas of the gift they’d gotten.

Every day in America, 20 people die while waiting for healthy organs. James’s decision to be an organ donor was unusual not just because he had been so young, but because just 58 percent of Americans follow through and tick that box at the DMV. “I didn't get involved with organ donation until graduate school,” says Tobias Reynolds-Tylus, PhD, a researcher who studies organ donation at James Madison University in Virginia. When he filled out the DMV form as a teen, he saw the spot where you could opt to donate your eyes. “I felt so uncomfortable thinking about my eyes not being in my body, I just didn’t sign up.”

Discomfort is just one of several barriers Dr. Reynolds-Tylus has identified in his research. Another is medical mistrust. “This idea of, ‘I can’t trust doctors, they’re going to steal my organs,’” he says. Of course, that’s a fallacy. Even if your driver’s license says you’re an organ donor, there’s a national registry that administrators must consult before your status can be confirmed. Doctors do not have access to that registry.

It’s also not uncommon for donors to hesitate because of the notion that the body should stay intact after death. And sometimes people just forget to sign up—leaving the box unchecked while they think about what to do, and then they don’t follow through.

Follow-through was not something James lacked. After switching to pre-med, he’d taught himself all the requirements to pass the MCAT (Medical College Admission Test). He became a Naval flight surgeon, but did additional air crew training so he could assist his team in the plane if needed. Of course he had checked the box to make sure he was an organ donor.

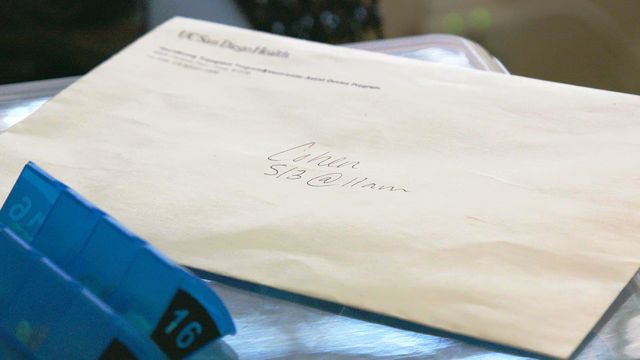

On March 19, Christine put the final copies of her letters in the mail.

Mike was trying to achieve some semblance of a normal life. It was early May, a little more than two months since the surgery, and he was finally back to living in a normal apartment, not a hospital room. Just as Christine had been told not to expect a response, Mike had been told he might never hear from his donor’s family. Some are simply too tightly wrapped in grief to reach out. But one morning, Mike got a call from the organization that had coordinated the transplant. They had a letter for him.

He unfolded the typewritten pages and took a breath.

Christine described her son’s love for serving his country, and the fact that he considered everyone a friend and never judged a soul. He was selfless, she wrote, had a quirky sense of humor, and was a brilliant and gifted doctor. She described his love for adventure, that he used his time off during a deployment in Japan to earn his scuba diving certification but also loved snowboarding and riding motorcycles. He was a frequent user of the phrase: “Go big or go home.”

As Mike read Christine Cheers’s letter, he began to understand just how special his new heart was. The average cardiac transplant recipient gets about eight years from their donated heart, says Dr. Shah. Reading the letter, Mike became determined to keep this heart as long as possible. “As cliché as it sounds, I wanted them to know that James’s heart was in a safe place,” he says. “That I was going to do everything I could to protect it.”

Since his surgery, Mike had spent a lot of time wondering about the man who granted him life every day. But until he read Christine’s letter, Mike had known nothing about the heart he got except that the person it had come from must have been exceptionally healthy. He describes his health upgrade as going from a Huffy to a full-carbon road bike—and strangely he found himself craving pizza, something he never had much of a taste for previously.

A curious thing that sometimes happens after a heart transplant is that recipients seem to take on one or two of their donor’s traits. Food cravings are particularly common. Dr. Shah says there’s no science to back this up, and never will be—you can’t make transplant recipients do a double-blind, placebo-controlled study on whether food preference transfers. But he estimates that between 20 to 30 percent of his patients report unexplained changes after the surgery. And he doesn’t dismiss it.

Regardless of the reason, for Mike, the change was marked and it was one tiny nugget he could grasp onto about this stranger whose life was now permanently plaited into his.

What Mike didn’t mention in the letter he eventually sent to Christine was that the plan he’d hatched in cardiac rehab was beginning to solidify. As soon as he was really and truly healthy, as soon as his doctor gave him the okay, he was going to ride across the country again.

Eager to know more about James, Mike typed his name into the Google search bar and learned that James had been buried in Jacksonville, Florida. The end point of his cross-country ride came into focus. Mike wanted to pay his respects in person. It seemed fitting to make the journey by bike—to show just how transformative the heart was. Go big or go home.

The trip would be slow. Not because Mike wouldn’t be fit, but because he had to be careful not to stress out his heart and immune system. Instead of 100-mile days like the last time, he began plotting a trip that would focus on fun: four hours of riding a day max, with his heart under 150 bpm, even if that meant crawling up hills. With a few days off in Tucson, El Paso, Austin, and Baton Rouge, he thought he could ride from the cardiac ward at UCSD to James’s grave in Jacksonville in just under two months.

Transplant patients take immunosuppressants for life, which prevent their bodies from rejecting the foreign organ. It’s well-documented that intense physical exercise can further weaken the immune system, making a person especially vulnerable to colds—which, in a transplant recipient, quickly can become very serious. So Mike recruited his brother, Dan (who had become certified as a medical assistant so he could care for Mike after his first open heart surgery), to tag along in an RV as support. Then Mike asked his friend Seton Edgerton to ride with him. This time, he wanted companions he could count on.

There is no manual for navigating a relationship with the man who has your son’s heart. No guidebook to figuring out exactly how you’re related to the family that literally kept you from dying.

Christine Cheers sent a total of four letters, one to each of the individuals who had received her son’s organs. She got a response from two. The first was from the man who got James’s kidney and pancreas. He thanked her, saying how the organs had changed his life—that he could go back to work and provide for his family. But his letter had subtly hinted that the thank-you note was all the contact he wished to have.

It took Mike a week to process Christine’s letter and another week or so to write back. He wanted to get the tone of his letter just right, to accurately express how grateful he was, how much this heart had changed his life, and how he was determined to keep it beating for years to come. He needed to communicate his desire to stay in touch with James’s family, if that’s what they wanted.

For Christine, Mike’s letter was a balm for a wound that had begun to feel like it would never heal. And so began the emails, the texts, the mutual Instagram stalking. The two were so similar, with their love of San Diego and adventure. And, yes, James had loved pizza as much as Mike now did. What were the chances they’d be so much alike? Christine didn’t know, but it was somehow comforting. Sometimes, she even read the captions Mike wrote on Instagram in James’s voice. “Knowing he was doing well really helped,” she says.

Even physicians who are schooled in science and facts and logic sometimes find themselves believing just a tiny bit in magic. Dr. Shah explains that when it comes to heart transplants, so much has to perfectly align. And in this case, it did. On the eve of Mike’s rotation to the bottom of the transplant list, suddenly there was James’s heart, in perfect health and an improbable 100 percent size and blood type match. The hospital where James had been taken after his accident was minutes from the facility where Mike was waiting. And James’s accident happened on Mike’s birthday—the day he blew out the candles and wished for a new heart. For Mike and Christine, the serendipity was profound.

By September, Mike was back to riding and building up his mileage. He hired Randall Fransen, a Portland-based coach, to build him a training plan. His physicians were impressed by his progress and his cautious approach—and ultimately gave their blessing for the cross-country ride.

Mike announced on social media that he was riding to his donor’s gravesite. The Cheers family decided they would meet him there.

Across Arizona, then on to Texas, Mike and Seton roll in matching blue jerseys, the struggles of that first arduous day behind them—at least Mike’s heart rate has settled down. Somewhere in the desert, they take a wrong turn and end up sloshing through deep sand. Somewhere in the middle of the country, Seton pins an American flag to his jersey. Somewhere in Texas Hill Country they get barbeque they still talk about three days later. In the first 1,000 miles, they get a combined 24 flat tires. Every time they fix one, another thorn or shard of glass seems to find its way into their lives. They try not to think about how many hours they lose to fixing flats.

From Florida, Christine and David follow along on social media, worrying about traffic and dogs and all the things that can befall a rider in the middle of nowhere. A few times, when Mike and Seton can’t find roads suitable for riding (or even just a direct-ish route), they detour onto the interstate.

“That’s illegal,” David, a former police officer, says to Christine when he sees Mike’s post about it. “You should tell them they can’t do that in Florida.”

Christine winces at the thought of semis whizzing by those boys, that heart. If it had been her son, she might call him and dress him down for riding on the freeway. But Mike isn’t her son; he is a stranger with her son’s heart.

On November 20, 2019, Mike and Seton leave the Flamingo RV Park in Jacksonville and pedal the last dozen miles of their trip. It doesn’t feel at all like the final day of his previous cross-country ride. “Last time, I was limping toward the finish,” he says while slathering thick white sunscreen onto his freckled skin. He warms up slowly on the road and thinks about what a gift it is to be healthy. How he doubted his body for so long, but how now he finally feels like there’s a normal life ahead of him. He ignores the niggling pain in his knee, and the fact he has the beginnings of a cold, and instead focuses on how well his body has handled this challenge over the past two months.

Mike’s nerves kick in as he get closer to the cemetery. He’s not so much worried about whether the Cheers family will like him or not, but about what kind of emotion may be attached to meeting strangers who have already come to mean so much to him. “It’s just such an intense moment to share with someone I’ve never met,” he says.

Christine and David Cheers get to the gravesite early. They want some time alone with their son before Mike arrives. It’s a perfect Florida winter day: sunny with a high of 72 and just a few passing clouds. They hear the whir of hubs as Mike and Seton coast into the cemetery.

Mike unclips from his pedals, hands his bike to Seton, and walks straight to Christine. At a loss for words, he manages a quiet “Hi.”

In that moment, Christine feels a deep sense of calm, as if she’s known Mike her entire life.

They fold into a deep hug. Then the tears start, silent and punctuated by a few sniffles. These are not the deep weeping tears of grief. They are tears of relief—from knowing that you’ve done right by someone you love, and from knowing that you’ve been accepted, or at least forgiven, by the family whose worst day was your best one.

The two release, and together they walk to James’s headstone. Mike squats down, balancing on the balls of his feet, and takes a deep breath, feeling the strong pulse of James’s heart in his chest. Silently, he tells James how thankful he is for his sacrifice, and how sorry he is they’ll never get to be friends. He promises to take care of his heart.

Someone runs back to the R.V. to grab the stethoscope from Dan Cohen’s medical kit. Christine Cheers slides the cold metal head underneath Mike’s blue jersey and listens. She shifts the instrument up, then down, and a little to the left.

Then there it is, loud and clear. The best part of her son still very much alive.