Over the past decade in New York City, more than 160,000 people have been struck by motorists. More than 1,600 have been killed. In 2019 alone, drivers have caused a staggering 20 cyclist fatalities in the city. Often missing from the uproar over these and other senseless deaths across the country are the nuanced legacies of those whose lives are cut short. Who were they? What did their lives mean? What potential has been snatched away? This story―a chronicle of the life and death of Robyn Hightman―reflects how much can be lost and the devastating impact on those left behind.

This story does not begin or end on Sixth Avenue. That heartbreak in New York City, which hardly defines the life of Robyn Hightman, will come soon enough.

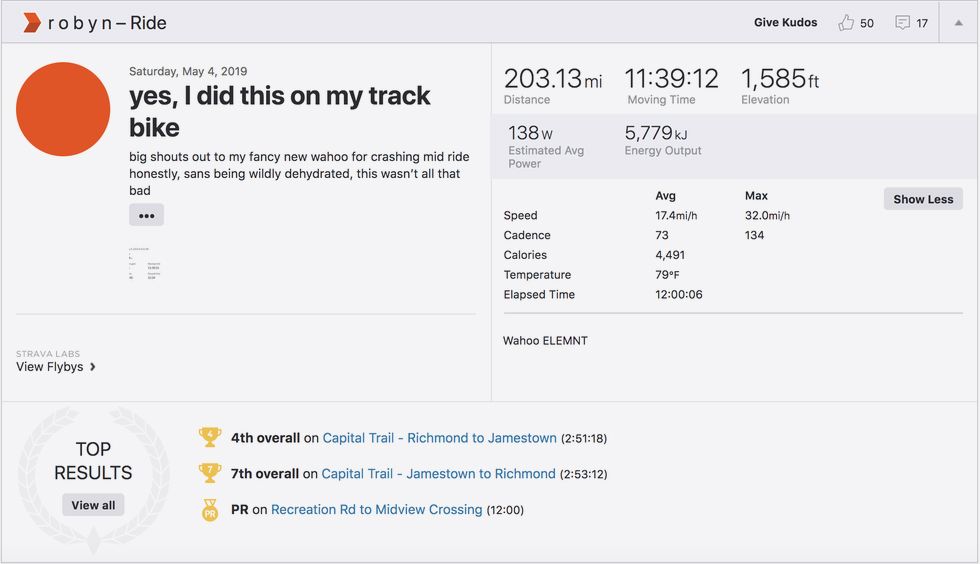

No, it’s more fitting if this story opens along the James River in Richmond, Virginia. It’s a Saturday afternoon in May, and the 20-year-old is piloting a track bike into Great Shiplock Park. Hightman―who chose to use the pronouns “they” and “them”―has been in the saddle for almost six hours on a hot day without a stop, and unclips before filling up a few water bottles. They’ve just finished a round trip on the Capital Trail, a multi-use path that connects Richmond to the state’s original capital in Williamsburg. Along that solitary 101-mile journey, Hightman has rumbled over more than 55 wooden bridges and ridden past freshly planted corn fields and found respite in long stretches shaded by sycamore and white maple.

This long day is going to get longer. Eight minutes later, Hightman arcs their black All-City Cosmic Stallion back onto the Cap Trail. Robyn will spin that 49x16 fixed gear until the sun goes down. The second century will be completed a few minutes slower than the first.

Imagine this young person, who two years earlier hadn’t ridden more than a few miles at a time, pedaling westbound after 10 hours of riding, still churning out 18 miles per hour—on track to finish an 11-and-a-half-hour double century.

That evening, Hightman would upload the 203-mile masterpiece to Strava with a simple comment: “Honestly, sans being wildly dehydrated, this wasn’t all that bad.”

People endure long bicycle rides for all sorts of reasons—to push themselves and to cleanse themselves, to find themselves and sometimes to lose themselves. Hightman had texted a friend two days earlier and expressed a desire to “ride bikes and suffer a little bit,” and now, cranking back into Richmond as the sky turned purple and then black, they were riding for all those reasons and at least a couple more.

Hightman’s last ride came 51 days later. It was the first hour of their second day as a New York City bike messenger. Hightman cruised northward on Sixth Avenue through Chelsea. It was a crisp Monday morning—June 24th, the fourth day of summer. At 9:16 a.m., Robyn picked up a parcel on Broome Street in Soho and turned onto Sixth somewhere around Prince Street. The dispatcher at Samurai Messenger Service had directed Hightman to head uptown toward the Flatiron District.

Hightman crossed West 23rd Street, and it’s an open question now whether the Freightliner box truck with New Jersey plates was behind them or to their left. Robyn was in the righthand lane, exactly where an experienced rider would set themselves up for a right turn unto 24th Street. Their next stop, a building on Broadway between 24th and 25th, was two blocks away.

They never made it. At 9:24 there was a tremendous thump and within seconds, two lanes of the street were littered with a smashed black Lazer helmet and other gear. Witnesses told reporters who soon descended on the scene that they’d seen Hightman’s body fly up into the air.

The first call to 911 came in at 9:25 and an ambulance was dispatched. Before emergency personnel arrived, construction workers rushed into the street to render aid.

The precise details of what caused the crash remain unknown to the public (as well as to Hightman’s family and friends). The NYPD’s Collision Investigation Squad has reviewed at least three video perspectives of the incident—there is a south-facing camera managed by NYDOT on a lamppost on the corner of Sixth and 23rd, and banks directly across from the impact spot on both sides of the street. Witnesses have offered accounts to the police and to media that may or may not all be accurate—that the truck was speeding, that a cab or ride-share driver pulled out in front of Hightman, that they were rear-ended or struck from the side. What is known from the police department press release issued the day of the crash and the subsequent certificate of death, is that Hightman was “struck and run over by [the] truck,” that the truck driver initially left the scene asserting he had no idea a collision had occurred, and that the driver was issued five summonses at the scene for inspection violations

By the time Kelsey Leigh rolled up to the crash site, around 10:00 a.m., Hightman had been loaded into an ambulance for transport to Bellevue Hospital. Leigh, a courier who was close with Hightman, had been dropping off a package on 45th Street when a friend called and asked if she knew a courier who rode a black All-City bike. She knew two and one of them was Robyn.

Leigh doesn’t exactly remember the ride down to Chelsea; she remembers repeatedly calling Hightman’s cell and the ringing that never stopped. But when she got to the taped-off crash site, Leigh observed things that she’ll never forget. “The first thing I saw was the blood, bright red and all over the street,” she says. “And then I saw the bike. I remember feeling like my stomach hit the floor as my eyes moved from the front brake, to the fork, to the bar ends, and the black bottle cage. All these unique parts that made up Robyn’s bike.”

The box truck that had hit Robyn was parked around the corner, so Leigh walked over with a friend. She says the driver, who was not arrested or charged in connection with the incident, was sitting inside a squad car, but the passenger was still in the cab. Leigh says her friend had a heated conversation with the passenger who claimed that Robyn must have fallen into the truck. “Robyn is one of the most steady riders I know,” Leigh says. “Robyn doesn’t fall.”

Like a lot of daily riders in New York, Leigh has concerns about how the NYPD has responded to the dangers that cyclists face on the road. And as she watched the police clear the crash site, she felt a growing frustration. “It all seemed very mechanical and quick, like they were just doing a routine operation,” she says. “I felt like they weren’t taking enough pictures, weren’t documenting the scene enough, not doing enough.”

Moments later, after walking me through details like the angle of Robyn’s handlebar and the positioning of the messenger bag, Leigh expresses a broader concern that’s making her sick: She can’t understand how drivers can hit someone and not feel it.

Robyn Avril Hightman was born on September 19, 1998, at Martha Jefferson Hospital in Charlottesville, Virginia. Jay Hightman, Robyn’s father, says his daughter’s name was a tribute to a high-school friend of his, Robyn Hess, who died of cancer when she was 19 or 20. He’d been devastated. “I said that if I ever had a girl, I’d give her the same name,” he says with his voice cracking.

From the start, Hightman was precocious. Robyn’s mother, Kymberlee (who asked that her last name be withheld for privacy), recalls taking her daughter for a well visit when she was three. “The doctor asked Robyn if she knew her letters,” says Kymberlee. “And Robyn wrote out her name—upside down so the doctor could read it easier.”

Less than two years after Robyn was born, Jay and Kymberlee had another girl, Rachel. When both girls were young, their parents split up and Kymberlee had custody of the children.

Robyn was an excellent student, taking AP classes at Charlottesville High, and had a busy extracurricular life. Kymberlee proudly recounts the breadth of her daughter’s interests. Robyn was an avid Girl Scout, a contra dancing enthusiast, and a flute player the Stonewall Brigade Band, the oldest continuously run community band in the nation.

Rachel says Robyn could grab a random instrument and quickly show proficiency. “She could pick up a piece of music and play it,” says Kymberlee. “She could draw and paint anything.”

Since childhood, Robyn had shown interest in helping others and had one day hoped to teach art to disadvantaged children. In their senior year, Robyn got into the art school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a program that’s typically rated among the top five in the nation. Robyn’s grandmother, Leena Miller, remembers taking Robyn for a campus tour. “She was just lit up,” says Miller. “But then she looked at me and said, ‘It doesn’t seem to be a good idea to take on $300,000 in debt if I want to teach art to inner-city kids.” In the end, Robyn turned down the slot.

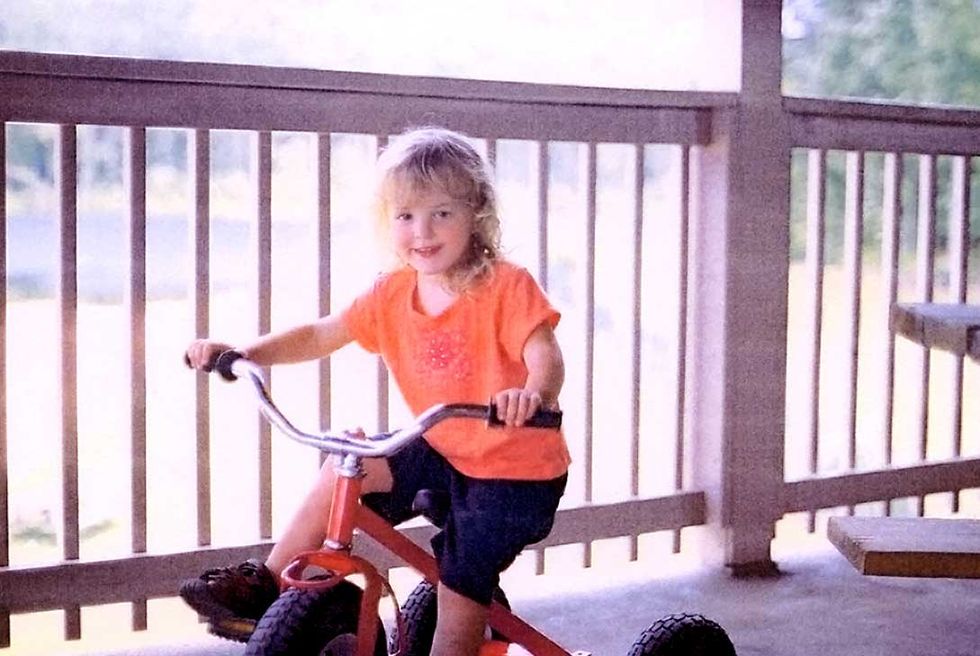

Like art, bikes were a part of Hightman’s life from the start. Robyn’s father had taken up cycling in a big way in the late ’70s, wrenched in a shop in the ’80s, and eventually got into tandem riding. Robyn started riding a red tricycle at the age of 3—and then graduated to a light blue kids’ bike he bought at Toys R Us. Jay remembers a shop visit when Robyn was in eighth grade. He got Rachel a mixte bike with tires that could go off-road, but Robyn lusted for a dark blue BMX bike. That’s the bike Robyn rode throughout high school.

Rachel—who says she last saw Robyn more than three years ago—describes summers with her sister in Charlottesville with some romance. “We had a pool pass, we had a library card, and we had our bikes,” she says.

Rachel is entering her second year at the University of Virginia and has become a regular cyclist herself. She says she understands the role the bike played in her big sister’s life. Rachel likes to train and do triathlons and appreciates the calming feel of a hard bike ride. “We only lived an hour apart,” she says, choking up. “And we never got to go on a bike ride together.”

Robyn had broken contact with several family members, but Rachel says she had hoped they would reconnect. Perhaps because Robyn’s intense passion for cycling developed more recently, some in the family feel Robyn’s engagement with bikes has been over emphasized compared with their childhood and adolescent interests. “Cycling is only two percent of her story,” says Kymberlee. “And 98 percent of it is still out there.”

The ghost bike is chained to a lamppost in front of the Sixth Avenue branch of Chase Bank. It’s a track bike with horizontal dropouts, no brakes, and a single 14-tooth cog.

It’s a week after an emotional ghost bike ceremony that took place four days after Robyn’s death, and now most of the bouquets are dried and fragile. A box holds a few dozen votives and a handful are still flickering. A Colnago cycling cap and one that says QUEENS are draped on the bike, as are a Bicycle Film Festival Staff lanyard, a patch from the DFL bike club in Richmond, and a tiny plastic unicorn with green hooves.

The bike was painted by Robyn’s friend Cheylene Tattersall and teammates on the Spin Peaks racing team, an inclusive crew of nine women who raced at the Kissena Velodrome in Queens. The day before they were killed, Hightman had been throwing it down in match sprints on the Kissena homestretch wearing the Spin Peaks kit.

Even for people who care deeply about the issue, the news cycle of these tragic deaths can be so rapid that the events can seem distilled down to 24 to 48 hours of intense mourning and then a preoccupation with the data—how many cyclists have been killed so far this year in New York, for instance. What’s missing from this dynamic is a deeper examination of what’s really lost in these fatal crashes—people like Robyn Hightman, whose lives and potential are cruelly cut short; the innocence of friends and family who are undone by grief; and the uncomplicated functionality and joy that everyday riders get from pedaling a bicycle.

Tattersall and other friends organized the memorial procession that rode across the Williamsburg Bridge from Brooklyn to lower Manhattan on June 28th, and then up to the crash site. Members of the Spin Peaks team took turns carrying the white bike. “I had it the last 10 blocks,” Tattersall says. “At the end, I walked it through the crowd of people who were waiting at the scene. It was intense—the closest I’ve ever felt to someone I’ve lost this way.”

On that emotional evening, friends and couriers and others in New York’s bike community came out in force to mourn together, to express love for Robyn and grief for the tragedy and anger at city officials who didn’t seem to be using their full powers to protect cyclists.

Exactly one week after Hightman was killed, a 28-year-old artist named Devra Freelander was killed by someone driving a cement truck in Brooklyn. And before July was over, three more riders were killed, bringing the death toll in New York up to 18 for the year, nearly double the total for all of 2018. (At the time of publication, the toll has risen to 20.)

As heartbreak and pressure rose among New York City cyclists, Mayor Bill DeBlasio introduced new measures—first a three-week crackdown on motorists and an initiative to stop ticketing cyclists after fatal crashes, and then a $58 million infrastructure program entitled the Green Wave—that represent positive but incomplete steps.

INTERACTIVE MAP: WHERE NYC CYCLISTS HAVE BEEN KILLED IN 2019

American cyclists have come to understand this duality. They know that if a few people die from a contaminated batch of arugula, government officials will take steps to fully contain the problem. Yet despite record numbers of drivers killing cyclists, the pace of upgrading infrastructure, legal protections, law enforcement, and judicial follow-through to make riders safer lags woefully behind.

One consequence of this duality is ghost bikes like the one chained on Sixth Avenue. Just a few feet north of that white bike are two signs—one stating the citywide speed limit of 25 mph and a smaller blue rectangular sign that says “Sixth Avenue SLOW ZONE.” The avenue is not congested on this particular morning and the flow of traffic is considerably faster than 25 mph.

About 48 hours later in Richmond, Virginia, I’m standing in front of a gnarled mulberry tree in Federal Park, where more than 150 friends had gathered on the night Robyn died. There are more votives and handwritten notes, photos and flowers, and a painted sign that says “Ride easy Robyn.”

Around the block on the corner of Rolland and Main, there’s a white-painted road bike festooned with artificial flowers and chained to a lamp post. It’s for another cyclist—Corey Frazier, a 21-year-old VCU student who was killed on this block in March 2018.

By the time of Frazier’s death, Robyn had been hit and injured twice by drivers and had become involved in Richmond’s advocacy efforts. “We’re a community,” Robyn said in a news article about the ghost bike installation for Frazier. “We know something like this could happen to any of us.”

A few hours after Hightman’s death was confirmed, the Hagens Berman-Supermint team posted on Instagram what it described as an excerpt from Robyn’s application essay for an ambassadorship with the team. In it, Hightman talked about the “independence” the bike had provided and said that cycling had helped them overcome numerous life challenges.

From the time of the Hightmans’ divorce until 2014, Robyn lived with Kymberlee in a rural area east of Charlottesville. But by the end of high school, Robyn had resided with more than a half dozen caretakers including Jay, family friends, a teacher, and eventually was in foster care.

Rachel McLaughlin, the high school art teacher who housed Robyn for a period, described Robyn as “broken” and said they wore makeup “like a mask.” One social worker who worked with Robyn during this time (and asked not to be identified) said that adults who cared for them “struggled with pushback.” According to friends who spoke to me for this story, Robyn regarded their childhood and adolescence as one of instability and struggle, which shaped their outlook on life.

Not long after graduating high school, Robyn moved 70 miles east to Richmond and began to assemble a new life—an identity shaped by art, bicycles, and new friends. Soon after the move, McLaughin visited Robyn. “I noticed for the first time she wasn’t wearing a huge sheet of makeup,” she says.

Robyn enrolled in the art program at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. Tyler Hurwitz remembers meeting Robyn during the first week in school. The two quickly became friends.

Robyn’s approach to art school was next level. Hurwitz recalls an early project where everyone was asked to make a monument. “Most everyone did something elemental with papier-mâché,” says Hurwitz. But Robyn quickly learned how to weld, and then fabricated an elaborate metal womb. For another project, Hightman constructed a 10-foot-wide loom.

Hurwitz says she overheard Robyn talking to a caseworker on multiple occasions about art projects. Hightman had qualified for a state program that provides educational financing to former foster youth. College is a stressful enterprise for anyone who’s financially insecure, but it’s especially tough for art students, where nearly every project requires costly supplies.

In the spring, Robyn decided to stop studying at VCU. Surely financial stresses played a role, but the truth is that during the course of that year in Richmond, Robyn had become passionate about a new interest.

Robyn’s love affair with bikes started on a Wednesday night. There’s this bike club in Richmond called DFL—the sort of punk urban bike community that’s flourishing in every American city, fueled by young people who are disconnected from traditional racing culture and instead seek adventure and experience on dark city streets. DFL does its big weekly ride on Wednesday nights, and one evening in the summer of 2017, someone split the crew into two squads and said that whichever team could return to Scuffletown Park with more random people on bikes would win.

Mohammad Jamali remembers that evening with a kind of reverence. His team was cruising past the corner of Lombardy and Grace Streets when they came upon a young woman riding a red Schwinn cruiser with a front basket full of yarn. Hightman pedaled with them to Scuffletown Park and went out the next night for a ride through a cemetery and became an instant regular.

DFL member Matt Segal met Hightman at Rag & Bones, a bike collective in Richmond’s Northside neighborhood, and they eventually grew close. “Robyn was riding the bike to get away from something,” he says, describing how Hightman had talked to him about foster homes and feelings of instability that defined their youth. “She had to keep pedaling to keep the crazy away.”

By the time Hightman formally became a member of DFL in June 2018, they already were working as a bike courier—first for Uber Eats and then for a Richmond-based company called Quickness RVA. That same month, Hightman recorded their first ride on Strava. In the following year, they’d ride 7,200 miles in 349 rides.

Couriers who worked with Hightman were impressed by how hard they rode. “They always went fast,” says D. Russell, who worked with Robyn at Quickness RVA. “It was like they were always training for a race. Which I guess they were.” There were funny moments, too, says Russell, recalling how Robyn liked to twerk on a cargo bike while singing along with the rap anthem “Tempo” by Lizzo and Missy Elliott.

Robyn demonstrated so much passion and competence that Quickness RVA owner Frank Bucalo soon made Hightman a de facto manager. They became a fixture at the Korean restaurant J KOJI, running point for Quickness RVA’s food-delivery enterprise. In the hours after the tragedy on Sixth Avenue, someone found a pair of Hightman’s shoes in the Quickness RVA office, and during the memorial ride that night, friends tossed the white-and-grey camo Converse All-Stars over the power lines in front of J KOJI. They still dangle above Robyn’s former command center.

Even though he was more than 300 miles away in Richmond, Robbie Wood knew Robyn was in trouble before some people in New York did. The photos of the crash scene were on social media, and Wood—the operator of Cyclus Bike Shop—can spot wheels he’s built a mile away. And there on Sixth Avenue where the hoops—with H Plus Son SL42 rims, All-City track hubs, and silver spokes—he’d laced for his friend.

Texts and emails and calls were flying around all the bike communities that Robyn was a part of along the Eastern seaboard. It was an excruciating hour or two.

Aware that specific responsibilities would fall to Robyn’s family, Cheylene Tattersall tracked down Hightman’s next of kin in Virginia. That night, Rachel and Kymberlee agreed that Robyn’s corneas, the only organs deemed viable, should be donated to a worthy recipient. Also that night, Cheylene attended a vigil ride that ended at the crash site, and the raw emotion and chaos of that event hit her hard. She came home and started planning a more reverential ghost bike ride and launched a GoFundMe campaign to help cover funeral costs.

The first thing that Kymberlee and Rachel did after arriving in New York on Tuesday was to visit the medical examiner’s family services center in New York to identify Robyn’s body. They were taken into a cold tile room, where a staffer put an image of Robyn up on a computer screen. Rachel couldn’t bear to look. Kymberlee, however, had no real choice. “It was a profile view—I think it was the best view possible. I could see that she had a scrape on the right side of her head,” she says. “It’s not something you’d ever want to do.”

The family was presented a death certificate that listed blunt-force trauma to the head and torso as the official cause of death. Then arrangements were made for Robyn’s cremation with money from the GoFundMe account.

Folks in the cycling community in New York and Virginia had hatched a plan to stage a ride from Brooklyn to Richmond with some or all of Robyn’s ashes as a way to honor and mourn their friend in what they felt was a manner that reflected Hightman’s own journey. But the family declined to part with Robyn’s ashes. “Robyn’s mother looked me in the eye and said we’re not leaving New York without Robyn,” Tattersall recalls. “That was a total rip-me-open moment.”

Kymberlee had no comment about the status of her daughter’s ashes, but Rachel said that her sister’s ashes would be stored in so-called living urns, where plants anchor their roots in the remains of a loved one. (Hightman’s friends plan to bronze exact replicas of Robyn’s Fi’zi:k shoes, which were recovered from the crash, for multiple memorials.)

Tattersall is philosophical about the situation. “Everybody needs an opportunity to mourn,” she says, mentioning how now, weeks after Robyn’s death, that she’s finding the space to mourn properly.

It’s worth noting that, given the uncertain circumstances surrounding the collision and allegations regarding conditions on the road, the incident could lead to a wrongful death suit by the family against any number of entities, according to some lawyers. “I have no doubt that it is a good candidate for a big civil case,” says Daniel Flanzig, a cycling attorney in New York who is familiar with the incident. “Even in the worst case, there’s no way it was Robyn’s fault.”

I spoke with multiple attorneys familiar with reported accounts of Hightman’s crash and all echoed that view—arguing that it was in broad daylight on a flat street, that cyclists are legally allowed to leave a New York City bike lane if it’s obstructed, and how it’s unlawful for motorists to enter a traffic lane if conditions aren’t safe.

Some news and police accounts in the days after Robyn’s death suggested that Hightman might somehow be negligent. A story on one CBS outlet indicated that “there have been no charges in the crash after police determined the cyclist was not in the bike lane and was traveling between vehicles when they were struck.” And a writer with Gothamist interviewed an NYPD officer who was ticketing cyclists the day after Hightman’s death a block from the crash site—a common crackdown tactic after fatal crashes in New York. “It’s sad, but it’s sad that she was off the bike lane, you know?” the officer reportedly told the reporter. “Maybe if she had been on the bike lane, maybe she’d still be alive.”

One afternoon, 10 days after Robyn’s death, I rent a CitiBike and retrace the end of their final ride, pedaling northbound up Sixth Avenue from Greenwich Village into Chelsea. I stick to the parking-protected bike lane (where parked vehicles provide a physical barrier to passing traffic) that lines the west side of the street. Along that mile-long stretch I encounter the following: open car doors, a couple skateboarders, trucks unloading goods, scores of pedestrians, a delivery guy pedaling southbound, about 10 construction zones, broken pavement, one police car, and a nice lady walking a pug on a retractable leash. It seems like a protected bike lane in name more than in practice.

Then I dock my bike and walk along Sixth Avenue, talking to street vendors, looking for someone who witnessed the crash. One man selling baseball caps across the street from the ghost bike says he was there when it happened. “It was awful and I don’t want to talk about it,” says the man, who has a Caribbean accent and declines to give his name. “I don’t want any trouble, you know?”

But then two vendors wander over and point to a steel plate, a couple inches thick and maybe 10 feet by 6 feet, that lies diagonally in the road. These are common in New York when crews are working on water mains or sewers—sometimes they have carefully graded asphalt edges to make them safer for cyclists and sometimes they don’t. The vendors told me that on the day of Hightman’s crash three or four of those plates were lying in the bike lane, and that city officials came around the next day and cited the responsible contractors. Within hours, they said, the plates were gone.

In my conversations with bike messengers and experienced urban riders in New York, everyone insists that skilled and fast riders like Hightman would almost always ride with the traffic on Sixth Avenue rather than tackle the crowded chaos of the bike lane. And veteran riders who knew Robyn dismiss any suggestion that Hightman was riding in the wrong place or acting recklessly.

“When you’re a messenger, your senses sharpen,” says Kit Melton, a friend of Robyn’s and a courier with Samurai. “You really get to feel the flow of the street. But that confidence doesn’t make you do anything rash.”

Perhaps no one embodies that sort of confidence more than Lucas Brunelle. The filmmaker and legendary urban rider says he first met Hightman at an alley cat race in Richmond a few years ago and shared about a half-dozen rides with them. “A lot of messengers either have skills or watts, but not a ton have both,” he says. “Robyn had traffic skills, navigation skills and tremendous speed.”

Two days after Hightman’s death, Brunelle posted an Instagram video containing footage of Hightman riding in New York with the simple comment “the angels came too soon.”

Talking about the particular chaos that led that box truck to hit Robyn, Brunelle states a dark truth: “Certain things can happen on the road where, in the end, it doesn’t matter how good you are.”

The filmmaker says that Hightman was like “the little sister I never had,” because of how they pursued their dreams and spoke their mind and rode with abandon just like he does. Robyn was not the sort of person to have death-bed regrets, he says. “I like that old proverb about the definition of hell—that on your last day on earth, the person you became meets the person you could’ve become and realizes the things you could’ve done,” he says. “Robyn didn’t wish she could do things—she just did things.”

Hightman’s network in Richmond was tight and deep, but something was pulling them to New York. Segal says Richmond is a kind of way station for young bike people he’s met over the years, a place for some school or a couple of years of work, and then they’d catapult to bigger things or at least bigger places.

Tattersall met Hightman in June 2018, when they were both volunteers at the Bicycle Film Festival, a New York-based event founded by filmmaker Brendt Barbur that celebrates bike culture through film showings, music, and art exhibitions. They hit it off instantly.

The next evening, Hightman mentioned sleeping on the A train the previous night. Tattersall told her new friend that they would definitely not spend that night rumbling out to Far Rockaway and offered up her couch. (For the festival this past June, Hightman rode a track bike from Richmond to New York—a three-day ride that covered 363 miles.)

Tattersall’s apartment became Robyn’s home base in New York. Tattersall also led the Spin Peaks team at the Kissena Velodrome where Hightman had started racing this past spring. Tattersall and other friends laugh at how Hightman expressed doubts about their potential as a track racer. Robyn’s initiation to the track came this past April during an event dubbed the 6 Days of Kissena, a contest spread over three weekends. “Robyn came out as a Cat 5 and just slaughtered everyone,” says Melton.

Tattersall—who says that Hightman felt like her little sister and brought “pure energy” wherever they went—saw her friend for the last time on the Thursday night before the crash. Hightman had gone to Cheylene’s apartment to eat a burrito and grab a helmet to use at the track after riding their first New York City courier shift.

I ask Tattersall if she remembers the last thing she said to Robyn that night. “No,” she says, starting to cry. “I didn’t pay close enough attention to that moment.”

Frank Bucalo and his wife had Robyn over for dinner the night before Hightman died. Bucalo is the owner of Quickness RVA, but moved to New York in 2016 after his wife got a job there; since then the longtime courier has been riding for Samurai.

During that dinner, Frank and Robyn talked about Hightman’s first official shift the previous Thursday and about the shift Robyn would ride the next morning. Bucalo thought Hightman needed a bigger bag, so he lent them a Road Runner Americano, a huge black backpack with compression straps and a blue liner that’s a classic among messengers.

They parted ways around 11:00 or 11:30—Robyn had to work in the morning. The last thing that Bucalo said to Hightman was “see you tomorrow,” when Robyn had planned to return the bag. “I’d usually say ‘ride safe’ to Robyn in a situation like that, but I didn’t say it that time,” he says with his voice cracking.

In the morning, Bucalo got a text from a courier who’d come upon the crash site around 10:00 a.m. It wasn’t clear yet who the victim was, but soon pictures of the bike and that big black bag were on social media.

Bucalo and his wife raced over to Bellevue and spent 20 tense minutes in a waiting room. They talked about the kind of recovery Robyn would face from such a big crash. “But then five doctors and a grief counselor came into the room and we knew it was more,” he says. At this point, a friend named Jose, who’d ridden across the Williamsburg Bridge with Robyn that morning—thus being the last friend to see them alive—was there, too.

After leaving the hospital, Bucalo, along with his wife and Jose, walked across town to the crash site. There he met a man who said he’d held Robyn’s hand until emergency personnel arrived. The man said he’d repeatedly told Hightman “everything is going to be OK” even as he took Robyn’s pulse and felt it fading away.

There remains a public perception that most cyclists are entitled hobbyists, but even normally privileged individuals who get on a bike can experience what it feels like to exist in the margins of society, where one’s right to exist without threats is frequently challenged by systematic animosity, flawed infrastructure, and inadequate legal protections. And for someone like Robyn Hightman—who had struggled to find stability in their daily life and who rode a bike as their primary mode of transportation and employment—that marginalization was exponentially more intense. Robyn had endeavored to find a safe place through riding and was denied in the most extreme way possible.

As I did the reporting for this story—talking to more than 30 people who knew Robyn well—one unexpected theme emerged: Every single person who rides a bike told me about getting hit.

Brendt Barbur, who founded the Bicycle Film Festival, was hit by a driver operating a bus in 2001—just seven blocks from where Robyn was killed. Robbie Wood was hit in Richmond—he was stopped at a traffic light and someone plowed into the car behind him. Richmond friend Brantley Tyndall got brake checked in 2016. Mitchell McKenna, another Richmond friend, says his bike got wedged under vehicle after the driver hit him from behind and police issued McKenna a citation. Frank Bucalo, who has a broken front tooth from a 2005 crash that he’s left unrepaired as a reminder, was hit last October by a pizza delivery guy in Brooklyn in an incident that left him with broken bones and physical therapy bills.

Jay Hightman says that he crashed in Charlottesville after a driver swerved into him. Rachel Hightman says she’s been hit a few times, and just 19 days after her sister was killed she was hit again.

Kit Melton has been hit and has lost friends, and now after Hightman’s death the veteran bike messenger says she’s too scared to ride. Melton’s life in New York has been defined and brightened by riding bikes on a daily basis, but now she’s planning a move to Colorado, where she can ride a mountain bike in the woods.

Melton asks to meet at a bakery in Bushwick. We were supposed to meet in Soho but she lost her subway pass and thinking about pedaling from Brooklyn to Manhattan overwhelmed her. She holds it together for maybe 90 minutes but now she is trying to express the loss and the guilt and the trauma of losing a best friend. They had a bond—both were bike couriers and track racers. “Robyn was the sister I always wanted,” she says.

Melton had wanted to go to Colorado for a long weekend in June so she asked Robyn to cover her Monday shift at Samurai. That shift turned out to be Hightman’s last. Melton hasn’t been able to ride her bike since then. “I’m in a big pit of despair and I can’t ride,” she says. “It’s shitty. My bike defines me and now I feel like a shell of a person, a scared person. It’s a weird place to be in—where the thing that gives me joy and strength and clarity makes me anxious. It’s super fucked.”

Robyn stayed at Melton’s apartment the weekend before they died. They saw each other there before Melton headed to the airport. Hightman had just completed their first full day as a New York bike courier. It had poured from morning until night, but Hightman had plowed through a nine-hour day without screwing up a single delivery or needing someone else to cover them. Still, Hightman questioned whether they’d been good enough.

“I told Robyn, ‘You need to believe in yourself,’” says Melton. “I mean, they did pretty damned great for a first day.”

“Oh my heart,” Hightman replied. “Thank you for your unrelenting support and for believing in me.”

And then they hugged. “I told Robyn ‘I love you,’ and they gave me the warmest hug I’ve ever had,” Melton says. “When I got on the plane a few hours later, I could still feel it.”

Melton was in Eagle, Colorado, on Monday morning when someone texted to ask what kind of bike Robyn had. Soon came an email from Samurai saying that they thought Robyn was gone. “I remember being in the mountains and just breaking down,” she says. “I felt so much grief and so much guilt.” In that moment, Melton felt so far from New York, so she walked out into the mountains and started gathering wildflowers. She found the skull of an elk and placed it under a tree and surrounded it with purple and yellow and white flowers.

I meet the guy wearing the blindfold right before I leave Charlottesville. Robyn’s grandmother Leena takes me down to the city’s historic downtown mall, the kind of outdoor promenade found in many college towns. It’s a late afternoon on a summer Friday and the wide brick walkway is pleasantly busy.

We stop at a storefront where Leena says that Robyn, as a junior and senior in high school, used to play the flute for money. Hightman had a basket with a little sign that said “college fund,” and often would jam with other musicians busking on the mall.

A block or two later we run into David, a man with white hair and a green T-shirt and a black blindfold. He’s standing with his arms extended like he’s waiting to accept a gift or perhaps to pray. Next to him is a sign inviting all passersby to share a hug—he’s not asking for money; it’s more like an offering of universal love from another era.

Leena says that Robyn and David knew each other from the period when Robyn worked on the mall. She steps into a hug with David and whispers that Robyn is gone.

When the hug ends, David pulls back his blindfold. His eyes are red. “She had some problems, but she was putting her life together,” he says. “She kept going.”

That’s what Hightman had been doing for years—pushing joyfully hard to move from one place to another. It was working. A new life defined not by the circumstances of their youth but by friends and bikes and candid conversation and raw energy and a desire to help people through art. Maybe Kit Melton put it best: “Robyn was going to do some shit.”

Back on the mall, David is rubbing his eyes. “The only things you really know are that you come into this world and go out,” says the man with the blindfold as he mourns Robyn Hightman. “All that matters is what you do in between.”