When Richard Boothman’s bike was stolen in 2014, it seemed like the universe was extending him an opportunity.

Then 59 years old, Boothman had only just rediscovered the joy of cycling. In law school, he’d ridden a sleek steel, lugged Schwinn Le Tour road bike. But after he started his family, cycling fell by the wayside. Old high school football injuries led to orthopedic surgeries which led to gained weight. After the kids left for college, though, Boothman started eating better, exercising more. He shed some pounds. He thought about cycling again.

His wife bought him a Trek Navigator—an aluminum comfort bike with bubbly 26-inch wheels. “It was a barge,” he says. “It felt like it weighed 30 or 40 pounds.” But Boothman used it to commute to work, and fell in love with being in the fresh air. When the Navigator was stolen, it was good timing. He had been thinking he might deserve a nicer bike anyway. He set aside $1,000—more money than he’d ever imagined spending on a bike. He was excited.

But then he started visiting bike shops. Five-foot-ten and (at the time) about 250 pounds, Boothman felt what he describes as “a definite snob factor” when he walked into the first few shops near his home in Ann Arbor, Michigan. “It was clear when I walked through the door that I was being typecast,” he says. Though he wanted something sportier, sales people kept directing him toward other comfort bikes, even trying to push him back onto a Trek Navigator.

Join Bicycling All Access for more cycling feature stories

One experience stood out in particular. A salesman, who was visibly annoyed to have to get a ladder and pull down the only comfort bike in the shop from the ceiling rack, started referring to Boothman as “Clyde”: “Hey Clyde,” he said, “why don’t you sign this release for your test ride?”

“I thought it was kinda odd, but I didn’t think much of it,” Boothman remembers. “About a year later, I learned people of my size are called Clydesdales.”

Boothman encountered discouraging treatment in almost every one of the shops he visited before he walked into Great Lakes Cycling and talked to owner Oscar Bustos. “In 40 minutes, I learned more about bikes from Oscar than I did from the six shops I’d visited prior to that,” he says. He ended up buying an $1,100 Cannondale Quick, and kept progressing his riding. By 2016, he was ready to tackle bigger rides. He bought a carbon Cannondale Synapse with Ultegra Di2. And of course, he bought it from Great Lakes Cycling.

“I Was Treated As If I Had No Right to Enjoy Cycling”

Richard Boothman found a bike shop that treated him with respect. But unfortunately, the experiences he had along the way are all too common. Unprofessionalism, poor customer service, and sexist and elitist treatment in bike shops has been well-documented on Yelp reviews, in articles, and on social media.

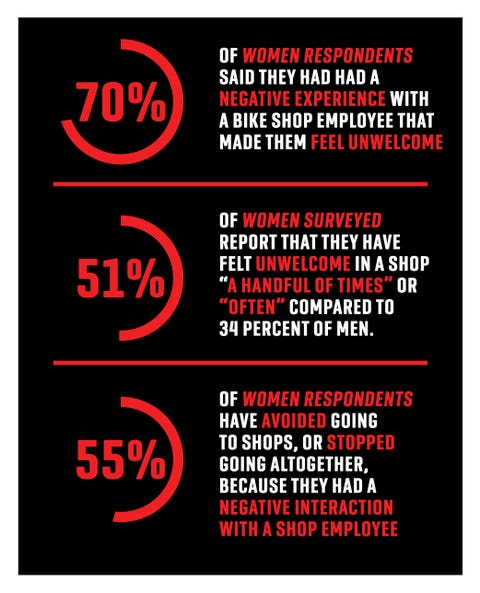

To gauge the extent of the problem, in January, BICYCLING conducted a survey about rider experiences in bike shops. Sixty percent of 718 respondents say they’ve had at least one negative experience with a bike shop employee that made them feel unwelcome. Thirty-eight percent say this has happened more than once, or “often.”

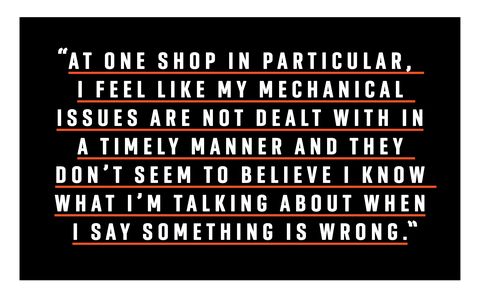

General condescension or snobbery was the most commonly cited behavior: “The bike shop employees...made me feel stupid for not being an expert,” said one respondent. Another said, “Shop employees tend to socialize with known customers. Until you’ve been to the shop a few times and made purchases, the employees tend to ignore you.” Other comments included being pressured into purchases or feeling looked down upon for having inexpensive bikes or being beginners.

Women have it worse: 51 percent report that they have felt unwelcome in a shop “often” or “a handful of times,” compared to 34 percent of men.

“It is really hard going into a shop as a woman,” wrote Sasha Lansky, a 27-year-old grad student in Somerville, Massachusetts. “I’ve been riding for 12+ years, I’ve worked in a shop, and I race at an elite level. I still have to spend at least 15 minutes shooting the shit with guys in a shop, dropping enough references and names of bike parts to earn their respect.”

Of course not all bike shops are bad. BICYCLING highlights fantastic shops all over the country on a regular basis. And some might argue that many negative shop experiences could be an issue of perception—behaviors like condescension, exclusivity, and even sexism are usually more subtle than outright. But bike shops are retail and customer service businesses, and they exist in a market where customers have alternatives: namely, the internet and even specialty stores like REI. When the survey suggests that the perception of being treated poorly in local bike shops is a common experience, that doesn’t bode well for shops.

Which is crucial right now, because bike shops are in trouble: According to the National Bicycle Dealers Association’s 2017 report, the number of independent bike dealers (IBDs) in the US has decreased from 4,256 in 2010 to 3,700 in 2016, a total decline of 13 percent. In some part, this has mirrored flat to declining revenues in the bike industry as a whole—an overall decline of 3.5 percent over the same period. But as with other areas of retail, the internet is the biggest culprit. Ninety-five percent of the 332 IBDs who participated in the NBDA’s study reported that internet competition is their number-one challenge. This includes bike sales from brands that employ direct-to-consumer models like Canyon, Trek, and Giant.

In light of these industry trends, local bike shops can no longer afford to not welcome every customer that walks through their doors—and need to do even more to attract new customers. The NBDA report draws a direct line between customer experience and shop sales: “Specialty bicycle retailers… are for the most part, neglecting the key aspect of retail—providing the excellent in-store experience demanded by customers. This has caused a significantly lower level of store traffic.”

Survey responses back this up: 56 percent of women and 44 percent of men have stopped going to a shop altogether because of a negative interaction with an employee. After watching a mechanic charge his friend $10 for a “brake adjustment” (no adjustment was made) to simply help him get the wheel off his Cannondale Lefty fork, one customer left this one-star Yelp review of a shop across the street from his house in San Francisco: “I used to stop in from time to time to pick up small tools and accessories, but after watching their attitude with my friend...I would never go back. It has been a shame looking at [this shop] while signing with the UPS guy for tubes, cable housing, and pedals.”

Shops that treat customers poorly aren’t only hurting their own bottom line. Bad experiences in bike shops can turn off beginners or anyone who doesn’t “fit the mold.” Fewer riders means it’s harder to advocate for better bike infrastructure. And because shops are invaluable social hubs for cyclists, if one closes, the local bike community suffers.

But there’s hope. While the number of IBDs declines, revenue per shop has increased at a rate of 23 percent over six years, suggesting that shops that survive can do well. We also spoke to several local shops who have reputations for great customer service, and which have reported year-over-year growth. They gave us some practical tactics for how local shops can grow and retain a customer base.

Of course the challenges facing bike shops are complex and multi-factored, and having great customer service won’t save all shops—one in a town with little bike infrastructure and fewer cyclists will be more sensitive to internet competition than, say, a shop in a market like Portland or Boulder. But getting up to the level of professionalism and courtesy that we expect from mainstream retail experiences seems a bare minimum of what bike shops need to do to survive in the age of the Internet, and to ask customers to “support local.” It’s time that bike shops give customers a local experience they’re willing to pay money for. It’s time for bike shops to change how they treat people.

“We Don’t Need Women’s Shops, We Need Beginner-Friendly Shops”

In October 2018, professional downhill mountain bike racer Amanda Batty went on an Instagram rant. Through live video, several screenshots of anecdotes from other cyclists, and a long post, she lashed out at what she called the “core/bro culture” of bike shops.

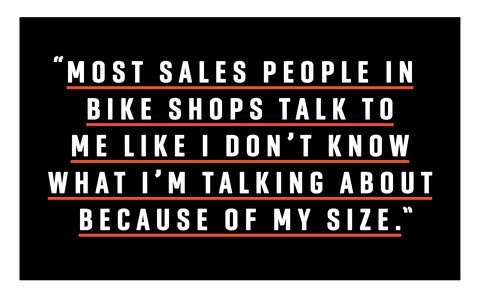

The term “core” is apt, because it’s not just women who are disproportionately treated poorly in shops—it’s often anyone who doesn’t look the part of a stereotypical fit male cyclist, or doesn’t look like they’re part of the “in crowd” of cycling. In the free form responses to our survey, weight was the second-most cited reason for perceived discrimination, after gender: “I am middle aged and large sized. I was treated as if I had no right to enjoy cycling,” said one white male respondent between the ages of 55-64. “Most sales people in bike shops talk to me like I don’t know what I’m talking about because of my size,” says another woman.

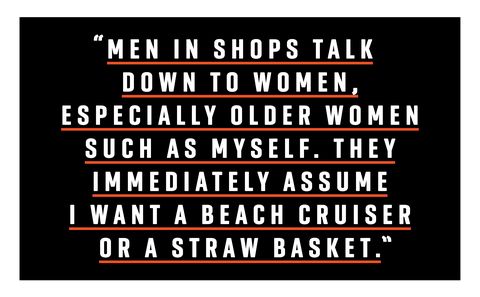

Older cyclists feel it too. “Men talk down to women, especially older women such as myself,” says one respondent. “They immediately assume I want a beach cruiser or a straw basket. Which is a shame as I own five bikes from a cafe steel bike up to a carbon road bike.” Another: “I am a fairly fit, healthy, female senior citizen and I have been biking for many years. I usually am treated in a patronizing and/or disinterested way...I am made to feel as though speaking to me is a waste of time.”

Sasha Lansky—the Massachusetts bike racer who feels she has to bro down with shop dudes to get respect—recalls being the only female employee when she worked in a bike shop in college. She’d see female students come in, looking timid, and get ignored by the male staff, who continued to joke around with each other instead of approaching the customers. When Lansky tried to tell her coworkers that they needed to go the extra mile to help women feel more comfortable, she was met with defensiveness. “They’d be like, ‘We’re not friendly, that’s not our thing,’ ” she says. “When you’re not used to being on the outside, you don’t know what it’s like.”

This insular, male-centric viewpoint can turn customers off in other ways, too. When Lisa Fleischaker, 38, of Costa Mesa, California first started cycling, she went into a high-end bike shop looking for clothing. The shop didn’t carry women’s apparel, so she tried on some men’s shorts instead. There was no dressing room, either, so she used the bathroom. “It was very obviously a dude’s bathroom,” Fleischaker recalls. “It was filthy and there were pictures of questionable, sexist cycling ads from the past. I was like, wow, I didn’t think I was stepping into this kind of world.” In other shops, she felt like she couldn’t get anyone to take her seriously: “I’m not a small girl, so I didn’t look like a skinny racer.”

Eventually, Fleischaker started her own shop for women, called The Unlikely Cyclist, in Costa Mesa, California. In her shop, employees are primarily women, and they’re trained to approach customers right away, and to ask questions. There are chandeliers and pillows in the dressing room. They stock a huge range of women’s apparel, including plus-size clothing, “because I want everybody to be able to ride.”

Fleischaker says that beginner men often tell her they wish they had a shop this unintimidating. “I don’t even think we need women’s specific shops, I think we need beginner-friendly shops,” she says. Fleischaker points out that other specialty retail environments do a much better job of welcoming beginners. “If I wanted to go get into rock climbing and I needed gear, the place I’d go to would be REI,” she says, citing the specialty retail chain’s friendly employees and lack of intimidation factor. “You think of REI as being this big love bubble of outdoor sports.”

“You Don’t Have to Discount If You Make the Experience Favorable”

BICYCLING’s survey of rider experience in bike shops held some good news for shops, too. Although the majority of riders had experienced poor treatment in shops, most of them (89 percent) said that they get professional or courteous service at their local shop, and 85 percent said they felt welcome at their local shop. It seems that when people do finally find a shop they like, they’re happy with the experience. This was true across gender and race. And respondents ranked IBDs as the number-one place they were likely to spend money on cycling-related purchases, with the Internet coming next, and chain stores like REI coming third. Sixty-seven percent of respondents also said they would be “unlikely” or “very unlikely” to buy their next bike online.

Cyclists are still willing to spend money at an IBD they feel loyal to. So which shops are attracting them, and what are they doing right?

The Unlikely Cyclist has seen revenue growth every year since opening its doors in 2012. Besides a welcoming atmosphere, Fleischaker attributes the success to hardcore community-building efforts.

“We have beginner rides, we have training programs, we train for a metric century that we put on every year,” says Fleischaker. “We hold clinics, from [how to fix] flat tires to how to climb a hill to how to shift your bike, and we run them...once every two months so we continually bring in new people.”

“We’ve built this following of women cyclists that come here, groups of friends, people who respect and love what we do. These women know they can get tires cheaper online. They’re not immune to that. But they would rather have us put tires on their bike for them, and support the shop, to have somewhere to come every Saturday. It’s almost like being part of a club and paying your membership dues.”

Events and community building are major opportunities for shops: Our survey shows that only 30 percent of respondents regularly attend rides or other events at an LBS. And just 57 percent said they felt like they were part of their local shop’s community—leaving nearly half the riders out there up for grabs.

An inclusive shop culture starts at the top, says David Guettler, 61, owner of Portland’s River City Bicycles, a big shop with 4.5 stars on Yelp and a national reputation for friendliness. “One of the things I tell my staff is, if I can’t have an attitude, no one else can, either. I’m a real stickler in that regard. I know there’s this grumpy curmudgeon type of mentality that somehow seems to be acceptable in our industry. That’s the stupidest thing ever.”

As for bike shops’ frustrations with seemingly clueless or demanding customers, Guettler says, “The thing is, customers don’t know. They may have an idea of how things work in a bike shop, but they don’t know. And we can’t assume they do. We can’t assume they know what our service schedules or procedures are, what we do and don’t do. And we just have to be gentle with them.”

“Customers, when they come in, they don’t really care if you’re profitable or what your inventory turn is or your payroll. They want great customer service, they want a great inventory, they want a well-stocked service department...What I’ve found is that you don’t have to discount your services or products when you make the customer’s shopping experience favorable.” Proof: River City never runs sales or markdowns. Yet last year, between its two locations—collectively, 24,000 square feet of retail space, including an indoor test track—revenue grew over 10 percent, says Guettler. They sell about 5,000 bikes a year.

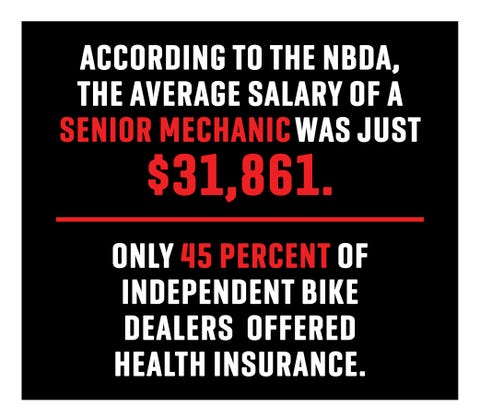

One major problem in bike shops: “Our industry loses really good technicians every day because of low wages,” says James Stanfill, president of the Professional Bicycle Mechanics Association. According to the 2017 NBDA report, the average salary of a senior mechanic was just $31,861; a junior mechanic, $23,413. And only 45 percent of IBDs offered health insurance. At those wages, even those who stick with it can get burnt out, possibly causing a grumpy attitude. “Some shops work really long hours for mechanics,” says Wes Weber, 29, a contract mechanic based in Boulder, Colorado. “As a mechanic [in those shops] you can feel like there's no flexibility to go sit down and have lunch. You see people walking around all day and you can't sit down. I think that's really hard for some people.”

To retain good employees who are highly engaged, Guettler offers his staff what he calls “living benefits.” River City pays their employees “just a tick over the market rate,” he says, but they offer health insurance, and a profit-sharing program (revenue-based bonuses) that can boost wages by up to $3 an hour. Nobody works more than four days a week or one weekend day. “We’ve made this more of a career place,” he says. “Most of our staff has been here 10+ years, some 20+ years...it’s a big financial commitment to have a really good service department. But I’ve always preached to my staff, as goes the service department so goes the rest of the store.”

Finally, if there’s one simple rule to follow, it’s this, says Sara Pearse, 30, of Greensboro, North Carolina: Just treat customers like people.

Pearse, who has been a professional soigneur on the WorldTour and now owns her own sports medicine and massage clinic, started working for a bike shop called Paceline Bikes at the age of 17. As a woman, Pearse has had experiences where she’s been dismissed both as a customer and a shop employee, but at Paceline, her male coworkers modeled good behavior. They treated each customer as an individual, and as more than just a potential sale.

One incident in particular sticks out. “This guy came into our shop. He was a big dude. He was well over 6 feet, probably 380 pounds. He was so big that he had actually broken the saddle [on his mountain bike] and bent the rails. The wings of the back of the saddle were folded down into each other. He had brought it back to the shop where he bought it and they laughed at him. It had obviously really hurt this guy. And I’m really glad he came into our shop because [my coworker] was like, ‘We’ll get you on tandem wheels, those will hold up better. Here’s a saddle with titanium rails that’s rated to a higher weight and a little wider.’ And I remember him saying, ‘Dude, your legs are gonna be so strong. Once you get out there and start riding, the weight is gonna come off, and you’re gonna be able to able to rip the legs off anyone on the trail.’”

“Watching this big guy, he came into the shop so diminished, and I just saw him have a complete turnaround in confidence,” she recalls. “That was a great example of how some shops can turn people away and some can build them up.”

“What a Difference My Shop Has Made”

Pearse’s story highlights how a respectful culture in a bike shop can have a real impact on the community. And Richard Boothman’s story shows that it’s also good for business.

Boothman has come a long way since his Trek Navigator got stolen. On the Cannondale Synapse he bought from Great Lakes Cycling, he’s tackled long rides, including a 40-mile adventure up and down the Leelanau Trail from Traverse City, Michigan to Suttons Bay and back. “That formerly would have seemed so daunting to me,” he says. He has lost over 100 pounds cycling. His cardiovascular health is “phenomenal.” “Even for a big guy, my numbers, my blood pressure, are great.” Along the way he continued to spend money at Great Lakes. His Synapse was $4,400 after he ordered custom-built wheels to handle his weight. He’s bought clothing and accessories. Most recently, he bought a $350 trainer so he can stay fit during the frigid Michigan winters.

Boothman retired a few months ago, and his newfound free time has opened up the possibility of multi-day trips. “I’m dying to ride from Miami all the way down to Key West,” he says. “We have friends in South Carolina, and I just started talking to them about three or four days in the Charleston area... I’ve got lots of ideas.”

Boothman found his shop when he was 60. “I’m now 64. And I’m thinking even more ambitiously.” He says having a good shop, with someone who was willing to educate him and treat him like a savvy customer, made a huge difference in his cycling journey.

Great Lakes Cycling closed in April, and in a quote to the Ann Arbor Observer, owner Oscar Bustos cited “personal reasons”—he said he wanted to spend more time with his family. But Boothman says that in the same month, two other local bike shops in Ann Arbor also closed—a grim reminder that the pressures facing the LBS today are powerful. Boothman is now on the search for a new shop, and has stopped by a few places, intentionally searching for his next cycling home.

“I’m a far more sophisticated customer now…thanks to [Great Lakes],” he says. “I want to get a feel for whether [my new shop is] willing to get to know me and my bikes, or am I going to have to reinvent the wheel every time I walk in.” One thing is for sure—when Boothman buys his next bike it’ll likely end up being from a local shop. “I’m looking for that personal relationship that you’re never going to get with an online bike purchase. [Oscar] didn’t have to sell me on that notion, that to have someone who knows you, knows your bikes and your riding, is a plus. It’s important to me, anyway.”

Gloria Liu is a freelance journalist in Golden, Colorado.