Kathryn Bertine has rarely met a challenge she couldn’t overcome. As Steve Friedman wrote in the September 2016 issue of Bicycling featuring Bertine on the cover: “Obstacles that stopped others, she clambered over, or rammed.”

It didn’t matter the sport, the time, or the place. When the Ice Capades urged 18-year-old Bertine to get a college degree before they would hire her as a professional figure skater, she went to Colgate University, where she was recruited to run cross country. When she didn’t get along with the track coach, she earned a spot on the rowing team. When the Ice Capades went out of business, she endured insulting mandatory weigh-ins as a performer for Hollywood on Ice.

When a road-racing crash left her convulsing on a road in Mexico, skull broken in two places, unable to hear a doctor say Nos dejando!—She’s leaving us!—Bertine survived. She makes a living as a writer, but doctors said she had to limit her screen time in 2016. Patience and inaction not being among her many virtues, she struggled to comply. She needed her brain to heal so she could write what she had to say.

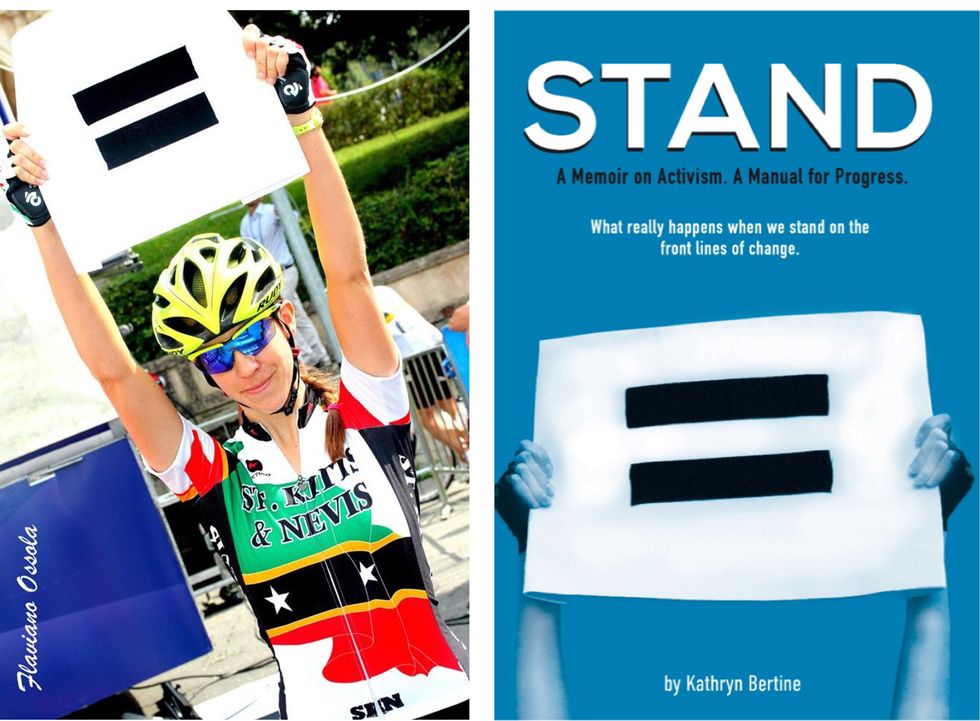

Most famously, two years before that crash, Bertine was the driving force behind a successful petition for a women’s race at the Tour de France. After years of unrelenting advocacy (for which she paid a great personal price) during which she simultaneously competed in the highest ranks of professional cycling, Bertine raced in the inaugural event she helped create, the 2014 La Course by Le Tour de France.

But at the very moment she should have been celebrating some lifetime-bucket-list victories, she went through a divorce and plunged into debilitating depression. She had just released a documentary called Half the Road: The Passion, Pitfalls & Power of Women’s Professional Cycling. But even as the film gained international distribution, amplifying the cry for equity in women’s sports, she found herself composing a suicide note.

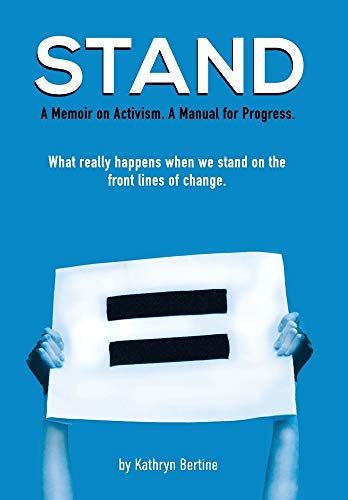

What happened between then and now—a story with a message that everyone needs to hear, regardless of gender or sport or cause—is Reason No. 1 to buy her book. It’s called STAND: A Memoir on Activism. A Manual for Progress.

Reason No. 2 to buy her book: The publishing industry said no one will.

“They all said a book about women who speak up and fight for change is not marketable,” Bertine said on the phone from her home in Tucson. “’Don’t bother. It won’t sell. ‘There’s no room on the shelf.’”

It seems fitting, then, that Bertine took this considerable roadblock and, through her personal alchemy, transformed yet another obstacle into an opportunity. She created an independent publishing imprint and named it New Shelf Press.

We caught up with Bertine to talk about overcoming obstacles and fighting for change—in cycling, women’s sports, and publishing.

Bicycling: You’ve done a lot of big things. Hard things. What’s the hardest thing you’ve ever done?

Kathryn Bertine: Combining activism and fighting for change while also being a professional athlete was the toughest journey I’ve ever been on. My first pro contract was racing for Colavita in 2013, the same year we were petitioning for La Course and also filming Half the Road. The Colavita athletes, owner, and sponsors were fantastic. But I received not just pushback but straight-up bullying from the team director. I was told to be quiet and not talk about all this equality stuff. Keep your mouth shut. “You’re a no one. You’re a nobody.” That’s a direct quote. It’s hard to hear those words. It’s twice as hard when they come from somebody you respect.

During the victory of creating/racing La Course by Tour de France and seeing Half the Road gaining international distribution, my private world erupted without warning. My husband left unexpectedly. At first, I suffered in silence. My personal life was falling apart at the exact time my professional life was taking off. I felt I had to be one person in public and another person in private. And that was a deteriorating experience for my mental health. Really brought me down to a level of depression I didn't know existed.

GET MORE GREAT READS IN YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY! 📬

How’d you get through that? How did it change you?

How I got out of that, essentially, was asking for help, both professionally and among friends and family. In retrospect, it’s very easy to say that asking for help is the best thing to do. But of course, it's very, very hard when you're in the throes of sheer and utter sadness, it's not as easy as it seems to ask for help. It’s not easy at all.

It has changed me. When I look back, seven years later, I wonder if I made it through all that to finally understand that vulnerability is strength. When we show that vulnerability professionally, and sometimes personally, it can actually strengthen who we are and what we do and what we believe in. But it’s hard to embrace that at first. Vulnerability is terrifying. It’s scary to let people know you're hurting. When you do expose those truths in the right way, to the right people, it’s freeing and liberating.

Does your experience as an athlete make you a better activist? Or does your experience as an activist make you a better athlete?

It was a blend of both—no doubt those two things are connected. Sound mind, sound body. Because I grew stronger as an athlete, it made me mentally stronger, more empowered to challenge authority. I think another important factor was age and experience. When I was taking on the Tour de France, I was in my mid- to late 30s. I was a little bit more aware and accustomed to the difficulties that women faced in terms of inequity or equal opportunity. These are things you learn as you grow older. I don’t know if I would have challenged or questioned authority when I was 22. But at 37? Absolutely. I had more life experience. And also made me a better athlete. Cycling is one of those endurance sports where women excel with age. At 22 I wasn’t as wise to the ways of the world or as physically strong as an athlete.

How did being a very outspoken, pulls-no-punches activist for equity in women’s sports affect your career as a professional athlete?

On Team Colavita, I raced one event in 2013, then I was benched for the rest of the season because I kept speaking out about equality for women in cycling. If you’re part of a team that adheres to UCI rules, it's illegal to keep an athlete from racing for more than five weeks. Meanwhile, we were making Half the Road. My director misunderstood the point of the film. She didn’t understand it was about all of women's pro cycling. She thought I was making a film about myself. When you’re working on a project that no one has seen yet, it leaves a lot of room for misinterpretation and preconceived notions. Unfortunately, the misunderstanding had a deleterious impact on my athletic career that year. When you're constantly called “a no one” it’s easy to start racing that way. Eventually, I would come back from this struggle and have the best year of my career at 40, but in 2013 and 2014, there was a lot of pain and hurting both on and off the bike.

You’re as much a writer as a rider. What’s the most important thing you’ve ever written?

This. STAND is my fourth book. I believe it’s the most important book I’ve written—and published—because corporate publishers rejected it. When my agent shopped the proposal, they all said a book about women who speak up and fight for change is not marketable. Don’t bother. It won’t sell. “There’s no room on the shelf.”

That’s not true! And it’s not OK for publishers not to invest in topics about equal opportunity. That’s important—especially now. I’m not saying I’m the important one. But can you imagine how many stories about women and minorities aren’t being published because of that?

It flipped a switch internally. We need to build a new shelf. So, I developed my own independent publishing label to put this out. I named the imprint New Shelf Press.

Who do you hope will buy your book?

I believe there are people who will stand with me on this, just like they stood with me on La Course and Half the Road. We had nearly 100,000 people sign the Change.org petition for a women’s race at the Tour de France. More than 600 people (from 16 different countries, equal parts men and women) crowdsourced $77,000 on Indiegogo.com to make Half the Road. That film is seven years old and I still receive royalty checks. That means people are still downloading and watching it. My hope is that one day I won’t receive royalty checks because we no longer need a film about women’s equality.

STAND includes a manual at the back. What’s that about?

STAND is part memoir, part manual... a book about what really happens when we fight for what we believe—and how to do it. I knew from the start that writing a book about activism needed to include both the personal story and the educational component. I hope that by the end of the book, people feel compelled to stand on the front lines for change. And if they do, they have a guide to going about it. I’ve never been a fan of how-to books that put a bunch of bullet points in the middle of a narrative. I’m the expert! Listen to me! That’s not my style. So, I put those tips at the back, knowing they’d make a lot more sense at the end of the story. That empowers the reader to decide whether they think I’m an expert on anything… [laughs].

What’s the main takeaway you want readers to get from this book?

I want readers to know that we are ALL capable of effecting change. We don’t need to be famous or wealthy, politicians or superstars. We, the common people, can change things if we find like-minded people and do it together. When I first started pestering and poking ASO [Amaury Sport Organisation, the French organization that owns the Tour de France], I was a solo voice in the masses. It wasn’t until I aligned with other people who shared the same viewpoint that ASO started listening. I joined forces with world champions and Olympians and other influential people. Alone, I didn’t have that clout. I was the runt of the litter. But I was the one who brought the game plan to the table. If some 39-year-old female athlete in Tucson can effect change at the Tour de France, we can ALL find our proverbial Tour de France and fight for the change we want to see happen.

You wrote this book after sustaining a near-fatal brain injury. What was that like?

In April 2016 I was racing in the UCI 2.2 Vuelta Feminil Internacional in Mexico, and in the final sprint there was a massive peloton crash, a multi-rider pileup, and I was on the bottom. I suffered a coup-contrecoup concussion—a severe brain injury due to the pinball effect when your brain gets slammed to one side of your skull and ricochets back to the other side. After five days in a Mexican ICU, I was air-lifted to Tucson, where I spent the next two weeks in the hospital.

I had just started writing a few chapters of a manuscript that would eventually become STAND. I had to put it down. Traumatic brain injuries affect people differently, but for me, it caused some limiting factors. One is fatigue. I needed at least 10 hours of sleep a night. Doctors limited my screen time, so as a writer I couldn’t sit down for a 5- to 6-hour spell of writing. As I wrote, there were times when my head knew the right word to use, but my fingers would type something different. I went to write “epilogue” but my fingers wrote “spillogy.” [Laughs.] After we hit the one-year mark from the brain injury, doctors gave me the all-clear to say I am now 99 percent as weird as I ever was.

A lot of people over the past four years have been awakened to activism and protest. What is the best way to make sure that energy doesn’t fade?

When we reach a milestone or see an improvement, it’s important that we celebrate that victory, but not grow complacent. We need to peel back the layers, flip over the stones of equality, and see what wriggles out from beneath. There are so many areas where things are not as good as they might seem. For example: Pay equity. There are plenty of areas where men and women are paid equally, but many areas where they’re not. The average doctor’s salary is higher for men than women. We won a big victory in the fight for a base salary for women pro cyclists. But it’s still not equal pay. We got a women’s race at the Tour de France. But it’s still a one-day race.

How far have we come since you started fighting for equity in women’s sports? What would you like to see happen next?

When I started fighting the Tour de France, I was the main voice. I was the squeaky wheel in the peloton. Not a lot of other women were as vocal or as comfortable in that role. Seven years later, I’m seeing a surge in the number of women speaking up. I see it on social media, in the formation of groups that challenge or question authority. I also see the media stepping up and asking these questions of the owners of sports. Now journalists are asking, “Where is the multi- day women’s Tour de France?”

We need to keep the pressure on. La Course is entering its eighth year in 2021. On one hand, that’s amazing. It shows the demand is there. But ASO has not kept their promise. They agreed to start with a one-day race, then add 3 to 5 days incrementally until we reached equity. They are keeping the women’s event at a minimum. Why? The demand is there from the fans, the athletes want to race more days, the TV and media is on board, and the return on investment of La Course is huge. The reasons are sexism and apathy. They choose to allocate their funds to other things rather than invest in the women. The more pressure we put on them, the more likely they are to change that.

Where do you get your energy?

I get my energy by taking negativity and flipping it around, then using it as motivation.

Follow @kathrynbertine on social media, and join her mailing list at www.kathrynbertine.com

Kim Cross is the NYT best-selling author of What Stands in a Storm, a narrative account of the biggest tornado outbreak on record. A national champion water skier, she has competed in more than 10 sports, some of them laughably obscure. She loves wheelies, dirt jumps, and riding in the snow in Idaho, where she coaches her son’s NICA mountain-bike team. Follow her at @kimhcross.