Every fall, pro road cycling’s biggest stars gather in Paris for the unveiling of the route of the next year’s Tour de France. Sawtooth stage profiles are scrutinized, the balance of summit finishes to time trials is debated, and odds begin to trade on the likeliest winners.

This year, for the second time, that gala event included presentations of both the men’s and women’s events, and a repeat TdF Femmes victory by Annemiek van Vleuten is the surest bet in the sport right now. But another rider is at least as likely to be the big success of the 2023 Tour. In fact, on that count he’s already won.

Mark Cavendish is, of course, a sprinter, who has no chance to take the yellow jersey even for a day on the 2023 men’s route’s hilly start in Spain’s Basque region. What he does have, however, is an excellent chance to win more stages of the race than any rider in history. And the story of that quest, which will begin to be told long before the July 1 depart in Bilbao, promises to be one of the most captivating storylines of the 2023 season. The only catch is a big one: he doesn’t yet have a team for next year.

More From Bicycling

Literally no other active sprinter in the sport has Cavendish’s resumé or experience. His 161 career victories have come in all kinds of ways in all kinds of races. Cav can slingshot off a leadout train as well as any sprinter, but his particular excellence is a kind of creativity when well-ordered plans fall apart. Other than Peter Sagan, no one “surfs wheels” as well as Cavendish, finds tighter spaces to somehow accelerate through, or is bolder about doing it (sometimes to disastrous result).

That also describes his 16-year pro career, with airy highs and trench-like lows in six stints on five different teams. Just as sprinting lanes open and close in the blink of an eye, Cavendish went from one of the most feared sprinters in the sport in 2016 to literal also-ran just two seasons later (a period during which he battled depression and illness). By the end of 2020, he was tearfully DNF-ing and would have retired if not for a late deal to return to Quick-Step—home to some of his biggest successes—for 2021.

You know the story then: the remarkable renaissance that saw him take four Tour stages and tie Eddy freaking Merckx for the all-time record of 34. And then his controversial absence from Quick-Step’s 2022 Tour roster despite fantastic fitness. The question now is whether one final opening will develop for 2023, a path to daylight to seek the stage wins record outright.

There are, on paper, a lot of reasons Cavendish hasn’t signed for a team yet. He knows his worth and likely won’t come cheap now like he did to Quick-Step in 2021, when a secondary sponsor reportedly paid his contract to give owner Patrick Lefevre one of the best ROIs in the sport’s history. And sprinters typically don’t travel light. At Quick-Step, Cavendish benefitted from dropping into the best-drilled sprint team in the sport, with arguably the best leadout man of the last 30 years, Michael Mørkøv. Replicating that takes time and a significant commitment to signing the riders to support it.

Those resources are hard to find, especially at this point in an unusually chaotic offseason. A three-year process to introduce a relegation/promotion system for the men’s WorldTour ended this year with its first winners and losers, and the aftershocks are still going through the system. After his departure from Quick-Step seemed assured, Cavendish was publicly linked to only one existing WorldTour team, EF Education, a courtship that ended in September.

The most likely landing spot was B&B Hotels, a French second-division team that would need a serious makeover to support Cav’s ambitions. The deal seemed all but done, with Cavendish reportedly getting fitted for team uniforms and ready to appear at a press conference in Paris the day before the Tour route announcement, but those plans were abruptly scuttled and rumor is now that the sponsor investment needed to close the necessary deals may not happen.

The latest suitor, at least if you go by social media posts, is Israel-Premier Tech, one of the teams relegated out of the WorldTour. Last week, Cavendish was posing for pics on an Ibiza cycling tourism junket with Rob Gitelis, founder of IPT’s bike sponsor, Factor. IPT itself is owned by Israeli billionaire Sylvan Adams, who unlike B&B team manager Jerome Pineau doesn’t need to wrangle extra sponsors to sign who he likes.

Maybe no team would benefit more from Cavendish’s presence than Israel-Premier Tech. The team wasn’t just relegated to the second-tier ProTeam level; by virtue of its low points total, it doesn’t even qualify for an automatic wild-card invite to the Tour. Adams himself has been publicly apoplectic about relegation, equating it to death and threatening to sue. But if Cav was able to resurrect his own career in 2021, he could do the same for IPT. But Cavendish has immense value to any second-division team.

Cavendish’s presence would all but guarantee a Tour wild-card invite, for one. And if there’s one truth about pro road racing, it’s that the Tour matters more than any other event to a team’s future, so signing him is a good way to ensure relevance in the sport. Further to that, the relegation clock re-starts in 2023. Cavendish, a points-scoring machine, would be a smart pick for any team aiming for a WorldTour license.

Most important, in terms of the media and fan exposure that is teams’ lifeblood even for billionaire owners, Cavendish is a win, no matter what happens in the Tour. A savvy, sophisticated communications team would immediately make the Drive For 35 the center of its PR strategy for the upcoming season, especially in documentary-style short films and social-media content.

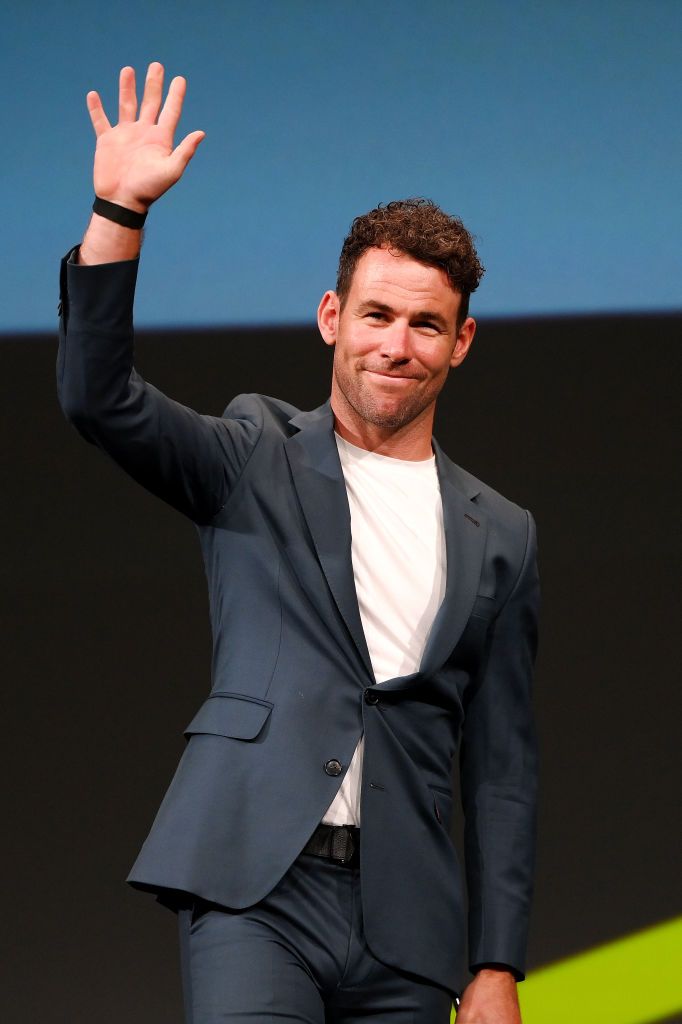

There are risks, for sure. Cavendish could get injured and be unable to race the Tour. It’s unlikely—but not impossible—that Tour organizers would snub his team as a wild card. And making Cav the center of your fan and media strategy raises pressure on him to deliver. Cavendish doesn’t much like external pressure, and when he’s feeling stressed he becomes a giant pain in the ass to deal with. Grouchy Cav isn’t exactly the best face for a big PR push; at the Tour presentation, Happy Cav briefly vanished when someone asked him about the wins record.

But those are surmountable challenges. You can get Happy Cav by appealing to his creative side like making him a co-producer on content and sharing story rights; giving him top-level support, including bringing on preferred staff; and setting his calendar for the best chances for success rather than just chasing UCI points. The Tour route, while difficult, may actually work to his advantage. The first two stages should settle the GC a bit, leaving the flat 3rd and 4th stages to sprinters’ business without the frenetic fight for yellow from other teams. Despite the route’s overall hilliness, there are three good chances for Cav to notch that 35th victory in the first week alone.

There are likely a dozen reasons Cavendish hasn’t signed a deal yet that I haven’t covered here or don’t know about: sponsor chess BS, unreasonable salary demands, administrative stuff like bank guarantees on team budgets, or just personality differences. But the fact that it’s almost Halloween and a rider who’s won five Grand Tour stages in the last two seasons and is poised to take the outright record for the most wins in the world’s biggest race—an absolute fairy-tale of a story—remains without a team is criminal. It’s one of those “This is why pro cycling fans can’t have nice things” stories.

Pro road racing is a deeply dysfunctional sport in many ways. But it’s also one that’s capable of delivering moments of transcendent, sublime beauty and emotion. Cavendish could author one of those moments in 2023. Let’s not spend the rest of fall wondering whether it’s even a possibility.