It’s simultaneously easy and nearly impossible to picture Primož Roglič—a man who has won two Grand Tours, whose improbable rise to the top of professional cycling over the past six years continues to stun the world—in an empty mall at night, cleaning escalators. The gray-blue jumpsuit, the headphones, the glitzy mall decor. On his hands is dark grease, the same inky color as his hair, and in the dimmed post-occupancy lighting, his bright, attentive eyes look out onto the atrium below, its windows black with the night outside.

“So…” he trails off, interrupting my thoughts with a chuckle, which becomes warped from the slight delay on the video call. “It was actually a good job. It was good pay, then.”

“Honest work,” I say, fully alert. He smiles and agrees.

I’d spoken with Roglič exactly once before this. The chuckling, the smiling, the eye contact, the almost unbelievable story about a mundane alternative path—he’d given me none of that then. What I got instead was the Roglič everyone in the press gets, the one who gives tight-lipped responses to post-race questions, answers that reveal nothing of himself.

“I’m looking forward to starting the season in Paris-Nice,” he had told me in February on a very expensive, staticky phone call from training camp in Tenerife, his voice completely devoid of excitement or joy or even life itself.

In March, between that first conversation and the second, Roglič, after spending most of Paris-Nice in the leader’s jersey, riding in a way that can only be described as resplendent, crashed on the final stage, crashed again, and lost.

I was viewing it from my sofa. My stomach sank as I watched him try to get back to the peloton the first time, his spent teammates of little help on the treacherous, winding roads, the timer in the corner of the screen showing a steadily growing gap between Roglič and redemption. I can still see that image of Roglič—his shoulder dislocated, his torn bibs revealing an awful spread of road rash encompassing almost his entire thigh.

And yet his face remained neutral, betraying no pain, no suffering. And yet he continued despite knowing that the endeavor was hopeless, that the peloton would not wait for him, that his race was over. And yet, and yet, in an act of sublime perseverance, Roglič finished the race, crossed the line exhausted and battered, but crossed it nonetheless. A month later he would go on to vanquish the competition in the mountains and in the time trial at Itzulia Basque Country, winning the six-stage race handily for the second time in his career. His failure became redemption.

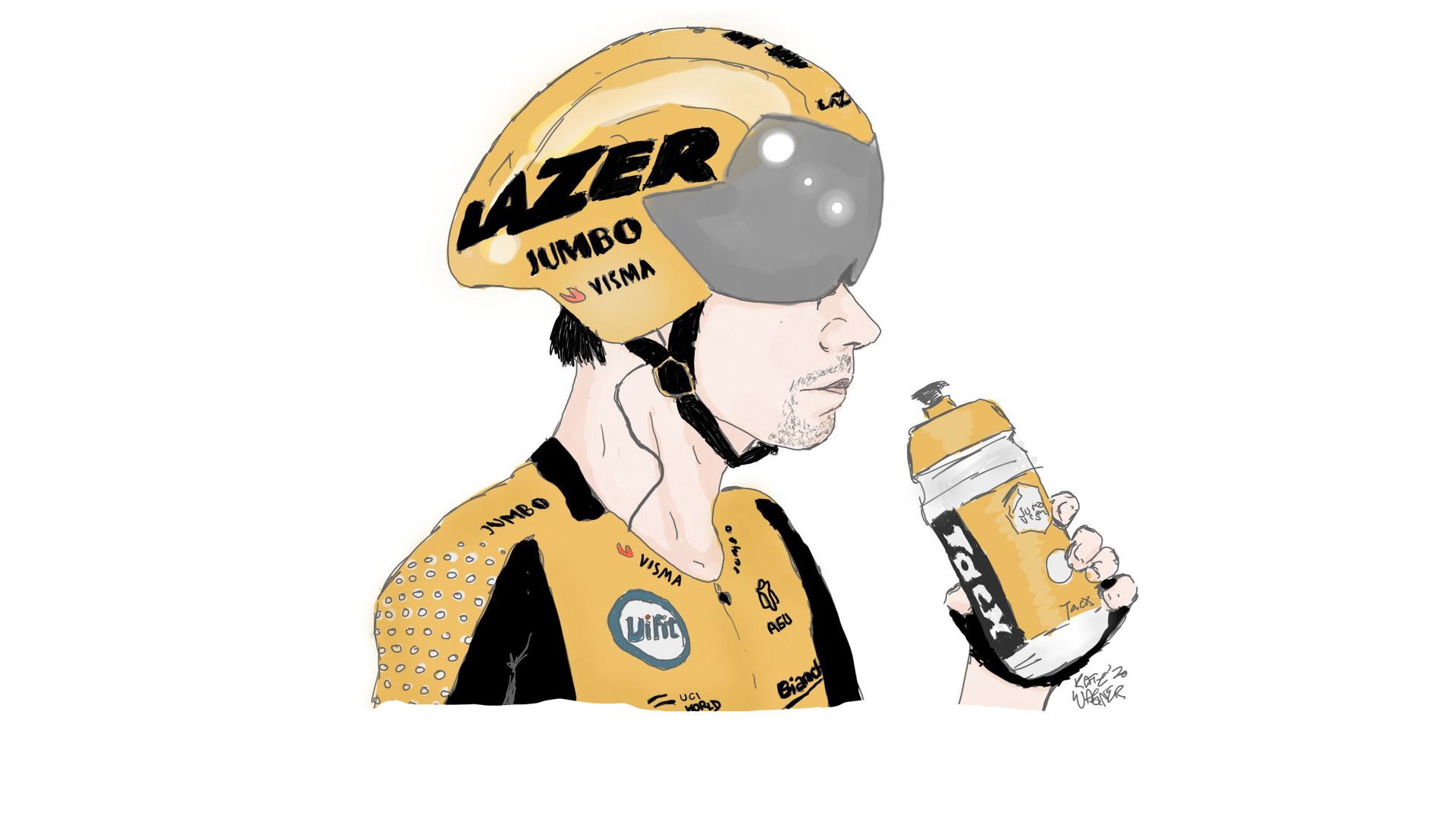

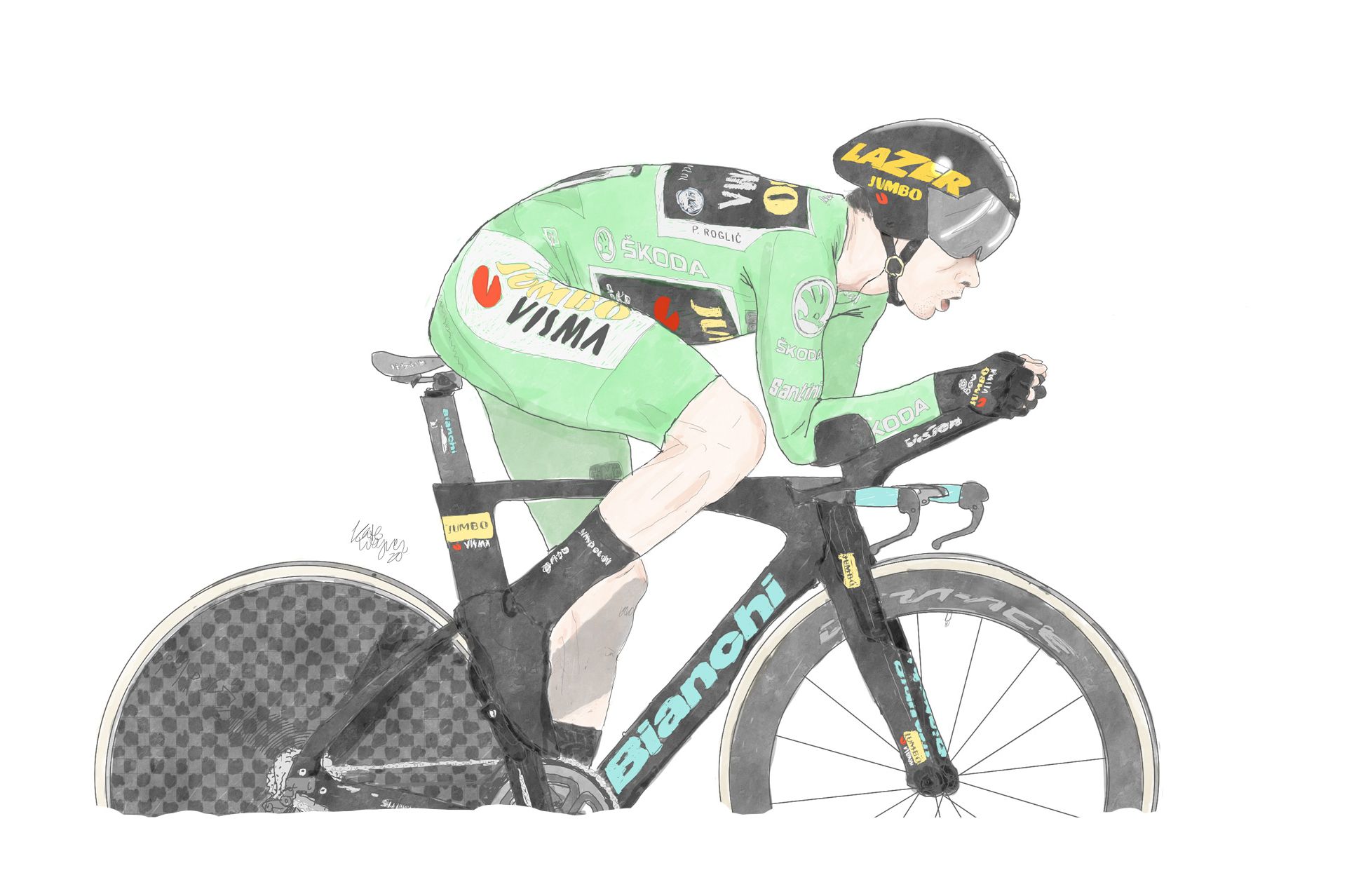

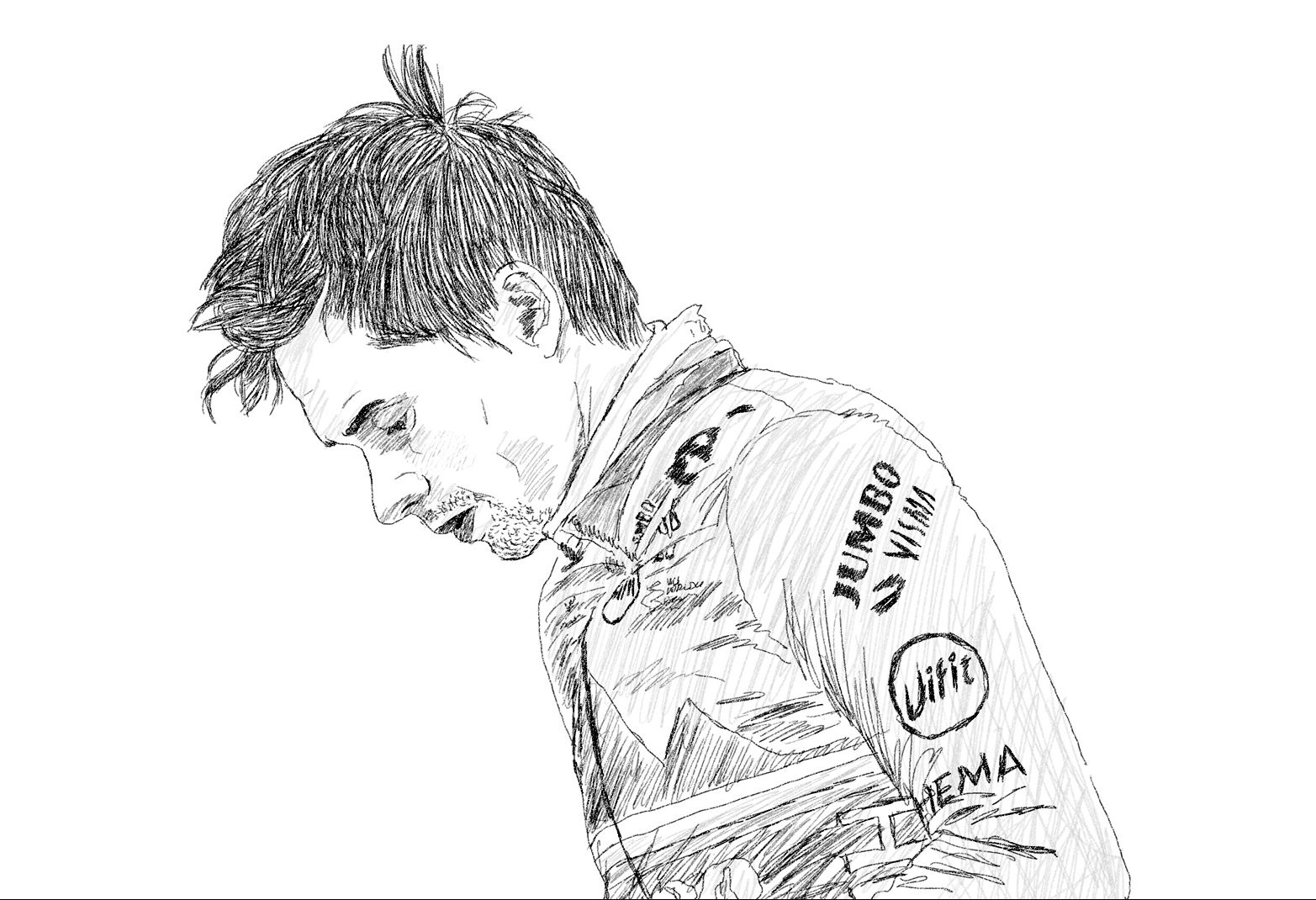

It’s a familiar scenario for the 31-year-old Slovenian rider. Just this past September, in one of the biggest upsets in 21st-century professional road racing, after two weeks spent grabbing the Tour de France by the scruff of its neck in a show of complete and total dominance, Primož Roglič lost the race in the final time trial to countryman Tadej Pogačar, his rival and friend. The loss stunned the cycling world, as did the sight of the normally impassive Roglič in abject shock and agony as he crossed the line, his time trial helmet crooked on his head. Suddenly, the Team Jumbo-Visma winning machine, a man the French cycling media accused of being about as engaging as a refrigerator, showed his humanity by walking up to Pogačar and embracing him, giving him his blessing before the entire world.

GET THE BEST OF BICYCLING DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EACH DAY! 📬

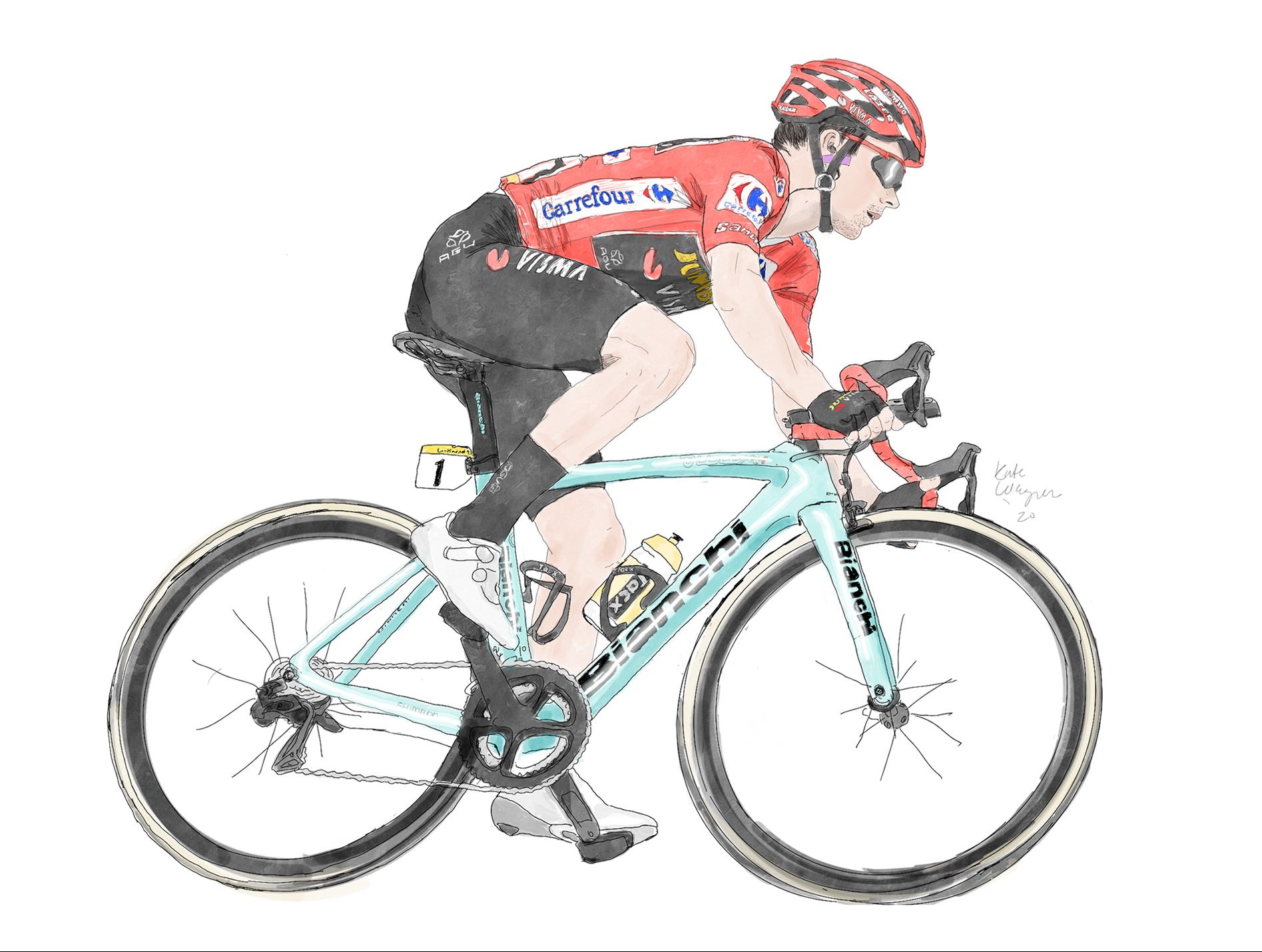

Most people would perhaps take some time to reflect on such a defeat, if not devolve into an outright existential crisis. But just 14 days later (thanks to the COVID-scrambled schedule of the 2020 season), Roglič would win his first monument, Liège-Bastogne-Liège, by pipping an already celebrating Julian Alaphilippe at the line in a memorable photo finish. A month later, he would defend his 2019 win at the Vuelta a España by managing to hold off Richard Carapaz by a mere 24 seconds after languishing on the final climb of the Alto de la Covatilla, a scene that had me screaming Not again, not again! in my kitchen. When he crossed the line, exhausted but victorious, all I could think was, Jesus Christ, I love this sport.

This narrative cycle of devastation and redemption lies at the essence of Primož Roglič. It is the common theme that ties his story together, the story of a man who failed at one sport before reigning supreme in another, the story of someone who answers defeat with feats of Herculean perseverance and remarkable self-discipline, a man for whom no adversity is too great to overcome. It is what makes him a hero to many—for people back home in Slovenia who find his working-class bona fides and small-town origins relatable; for young and amateur cyclists who are inspired by his feats of athleticism and by his success at a relatively late age; for his nearly 500,000 combined social media followers; and for cycling fans around the world. And it’s a story that for me hits surprisingly close to home.

As the story goes, Primož Roglič was once a competitive ski jumper, realized at 22 that he wasn’t going to make it, and, after a seemingly miraculous transformation, rose to the highest ranks of professional cycling. This, of course, is a simplified fairy tale, but it has a universal appeal. Who hasn’t felt trapped by a chosen path and dreamed about an alternative, or even taken that step? Who hasn’t hoped that deep down within lies some undiscovered superb talent?

I have. From the age of 4 I’d trained to be a classical musician, realized at 22 that I wasn’t going to make it, and then, in a seemingly miraculous transformation (a blog going viral), became an architecture critic. Then, on the heels of Roglič’s glorious and heartbreaking performance at the 2020 Tour de France, I discovered that I loved writing about this sport more than I loved writing about anything else. I loved the literary drama and the eclectic cast of characters and the freedom to tell sprawling, emotive stories. And the more I wrote about it, the more I started to dream: Maybe I could be a correspondent for the Tour de France someday, maybe I could write a book, maybe I could spend my time talking to these fascinating people who labor in such visceral ways beneath a blistering sun pushing two wheels up the sides of shaved mountaintops for a living. Primož Roglič’s story had become a defining narrative to me, and I found myself contemplating his feats of self-discipline and persistence during some of my most existential moments.

But as soon as I accepted this assignment, I knew my task would be difficult. I’d been granted just one 30-minute phone call with Roglič during that team camp in Tenerife. The closer the day came, the more out of my depth I felt. Here I was, about to interview the number one ranked cyclist in the world, this person I’d watched breathlessly on television, whose life had become this strange, cherished inspiration to me.

A few days before the call, I scanned the spines of the books on my shelf, all of which are about architecture, and in that moment I felt a kinship with the riders in a road race who leap off the front of the peloton to try to join a breakaway far up the road, an endeavor they know in their hearts to be doomed, but at the same time they have to try. Un chasse patate, chasing potatoes, as the French call it. Our sport’s version of tilting at windmills.

On its face, the whole scenario seemed absurd. Delusional, in fact. Consider Roglič’s well-established history with the press. Language barrier aside (his English, while improving, is still middling), he usually comes across as fussy, cold, and unapproachable. He gives the same handful of answers so religiously that he seems like one of those dolls with a string in the back; pull it and he’ll deadpan variations of: “Good legs, good guys today, yeah.” “We shall see, huh?” “Tough stage, very good job with the team and the results.”

That Roglič is a hardened man, quietly ruthless, an enigma, a winning machine. In front of the cameras, he is stubbornly neutral and occasionally curt, though never combative outright. He knows the interviews are a pointless formality, and he treats them as such. The things he says are infuriatingly obvious, along the lines of, “If you want to win, you have to be the best.” This grants him a mystique that makes him a tantalizing literary subject—people like that exist for writers to decipher. Few have succeeded.

Cycling loves its underdogs who become legends, its hardmen. It’s a satisfying depiction, one that fits a narrative of a sport still tinged with old-school machismo. Empathy for Roglič comes only when he loses, when he shows weakness. Some of our only glimpses of the man underneath that icy facade came from last year’s Tour de France, when the combination of exhaustion and shock made him unusually vulnerable. As soon as he started winning again, he was back to his usual talking-doll ways.

There are reports of a secret Roglič, a private Roglič who is warm and funny and outgoing, a Roglič purported to be antithetical to the one he shows the press. His partner, Lora Klinc, once remarked: “There are two different Primožes. One is a cyclist, and one is normal Primož.”

I wanted to be the writer to crack Primož Roglič open and reveal to the world his true self, the Roglič his friends, family, and teammates swear is under that enigmatic, impassive exterior. I wanted to put an end to the hypermasculine narrative of the legendary hardman and replace it with a more emotionally complex one, a sincere one, one that wasn’t so replete with the tired stereotypes of cycling born from a desire to see men as strong and dominating above all else.

I spent weeks keeping a journal, pouring my heart out to friends, saying maudlin things like, “This piece could make or break me.” At night, before going to sleep, I would scheme feverishly, devising questions that might get this notoriously uptight person to be vulnerable. Perhaps if I offered some of myself, of my own life, he would do the same. If I could simply be different from his other interviewers, then perhaps I would get different responses out of him. In my dream scenario we would build a rapport, and through a tactful combination of empathy and selflessness I would be the one to finally unlock the icebox that is Primož Roglič.

After a sleepless night spent agonizing over the nuances of the whole thing, I arose anxious and foggy, found his name on my contacts list, bit the bullet, and called.

It did not go well. It was a terse, tense conversation, full of silence and evasion. From the second he answered the phone sounding tired and gruff, I was terrified of talking to him, and I knew this would not go as planned.

I ran out of questions midway through and ended up asking stupid things off the cuff, like what he thought of Jumbo-Visma’s switch to Cervélo bikes (“We will see with the races”) and recent UCI rule changes (“...at the end I just have to accept and respect it”).

The highlight of our chat was a story about his first race, in which he said he was too frightened of crashing to take food or drink and rode 170 kilometers clenching the handlebar in terror. I only got that out of him by offering a tenuous analog to his own narrative, about how I quit music school after realizing I wasn’t going to be competitive. When he responded, “at the end maybe we both figure it out,” it was unclear if he was sincere. And after that fleeting moment of conciliatory weakness, he soon zipped his lips once more, returning to his safe, wooden responses. It was agony.

Near the end, I started to regain a little confidence after a series of truly frustrating non-answers and said, “I’ve always gotten this feeling that you’ve been portrayed in this interesting way by the press… That there’s the person you are to the public and the person you are behind the scenes. Is that an accurate picture?” I added, “Or is it just that you’re entitled to have a private life outside of cycling and people find that to be a little disappointing?”

He laughed, a rather dark chuckle.

“Yeah, well, you will never know, huh? You will never know.”

I hung up, my hands sweaty and shaking. I knew I had binned it, binned it worse than Roglič binned that descent in the final stage of Paris-Nice. A certain writer’s desperation filled me. I listened to the shoddy recording, searching for something, anything of significance. I read things into his responses that weren’t there, because frankly he gave me nothing. I called my editor in a manic frenzy. Afterward I rode my bike on Zwift until I felt like puking, lay in bed listening to sad music, and tried not to cry.

I rued my naivete and journalistic cowardice, of course, but deeper down I didn’t understand how someone who gave so much of himself to the sport seemed to care so little about it, or about anything. Cycling is known to be a sport of great passion, and for one of its most glorious participants to treat it as lifeless and dull seemed unfair, unflattering, and unheroic.

I didn’t want to write about the Roglič I had just met. There was nothing new to see or describe; I could have popped any post-race interview into the transcription software. I didn’t want to churn out yet another profile depicting him as the same stoic, taciturn, fierce competitor feared by everyone in the peloton, a man watched with apprehensive eyes as his foes anticipate another one of his sickening attacks. Worse, I didn’t want to write about the Roglič I had just met, because I did not like him. I realize now that in some ways, that disastrous phone call marked my transition from cycling fan to working professional. But it also sullied the idealistic image of Roglič that I’d held so close. And I very much wanted to like him again.

One thing was certain: I needed another chance—not only to extract the biographical information I could only get from Roglič himself, but also to redeem myself from what, at that time, felt like an almost certain failure.

When I look back now with a more lucid and practical mindset, I ask myself: Why did I want to like him? Why exactly did I want this man to reveal his true self to me in the first place? Was it to prove to myself and others that I am worthy and legitimate as a writer, a sportswriter, as a journalist? Was it to take satisfaction in being the kind of person that quiet, withdrawn people reveal themselves to? Or was it because beneath it all, I admired this man and used his life as a model by which I lived my own, and therefore I feared being disappointed by him? There’s an unflattering truth to each of these things.

I’d have to wait three months for my second chance, but on May 8, a week before this piece was due, Jumbo-Visma emailed and told me to make a Zoom link for the morning of May 11.

Again, I didn’t sleep. I debated what items I should keep in the background of my office. Pinned up behind my time trial bike on the trainer is a jersey from the 2019 Vuelta, signed by Roglič, an inspiration to pedal faster. I almost took it down.

When he answers the call, he’s at training camp, sitting in a hotel in southern Spain, his face bright pink with a wicked sunburn. He’s wearing a Jumbo-Visma T-shirt and trucker hat, the camera making the yellow bill seem oversized to the point of comedy. He turns the sound down on the television, and before I can speak, he says, “I see you have a nice jersey behind you.”

“That one’s signed,” I tell him. “That’s… that’s yours.”

He laughs. “Nice,” he says. The ice melts. I tell him about the profile, what it’s for, joke about how the U.S. doesn’t care about pro cycling unless we’re winning, tell him that I hope to tell his story with this piece, and by doing so, get people interested not only in him but in the sport.

“We can try and do our best,” he says, “and then, we’ll see, huh?”

I let out a deep breath.

“Okay. This time I want to start at the beginning.”

Primož Roglič was born in 1989 in Kisovec, a small village of “30 people or whatever” on the outskirts of Trbovlje, a city whose best-known exports are coal and the avant-garde industrial band Laibach. The tumultuous years of Yugoslavian disintegration and Slovenian independence occurred when Roglič was a child and, insulated by the sleepy life in the country’s central foothills, he has no memory of them. He’s the only child of a working-class family. His father worked in a factory and his mother, a former schoolteacher, is currently employed as an assistant in a dental office. Neither of his parents are athletes, nor were they particularly interested in sports, but he notes, “They were always supportive of me, of anything I did.”

A child with “a lot of energy,” Roglič had always gravitated to athletics. His parents signed him up for his first sport, soccer, when he was 6, “just to do something.” Later, in his early adolescence, he took up ski jumping largely because it was convenient: His neighbor was a coach and there were facilities three kilometers from his house. Roglič reached quite a high level in the sport: In 2007, at age 17, he won a gold medal in the junior world championships. Shortly after that, on the perilous slope at Planica, he lost control and tumbled like a rag doll down the agonizingly long hill. That was the beginning of the end of that arc of his eventful life.

He sold his motorbike, bought his first road bike, and started riding gran fondos and short local amateur races (mostly hill climbs), sometimes two a day. There’s a photograph of Roglič from that era, around 2011, dressed in an old FDJ kit and white sneakers on a cheap mountain bike (complete with kickstand), a look of pure grit on his face. Behind him is a small group of decked-out roadies, languishing.

“That was really the start,” he says. “I borrowed the bike from my neighbor. Another neighbor gave me some cycling kit that I put on.”

“The FDJ kit.”

“Exactly, yeah,” he says, laughing. “I just went down behind the house, and we had that kind of race and I went for it, yeah?”

“Did you win that race, with the mountain bike?”

“Not that one, but that year, when I had a road bike, I already won [some]. Still, I was not the last one,” he adds. “I still passed a lot of guys anyway.”

“When did you realize that you could do this professionally?” I ask.

“I didn’t know what could happen, the obstacles, how hard it actually is,” he says. “I just wanted it. I had a dream.”

He goes quiet, and then he tells me something rather astonishing. “Still, when I am thinking back, if I had known how hard it is… it’s a really hard decision. Maybe I would never even start riding a bike. But by not knowing…” He sighs. “Yeah. I had nothing to lose. I could just try and see.”

When I had asked this same question in our first conversation, Roglič told me that he quit ski jumping because he wasn’t the best, wasn’t world or Olympic champion by the age of 22, so he decided to walk away, choosing cycling instead because he thought “it would suit me really well.” However, the truth is more complicated.

In reality, Primož Roglič, in the first few years of his 20s, was something of a lost soul. A drifter. He may have been a high-level ski jumper, but that was never something he did full time, and it certainly didn’t pay his bills. He was also enrolled at the university in Kranj, where he chose a practical major, organization and management. He describes himself as an average student, “not the best of the best, but also not one of the stupidest ones either.” He attended five years of university (“one year at a time”) but didn’t quite finish, something he still hopes to do. Meanwhile, he worked odd jobs to make ends meet, sold cleaning products door to door, scrubbed escalators in malls after dark.

“There’s a story, right?” I ask. “You basically emailed out of the blue, like, ‘I want to be a pro rider.’”

Roglič nods. “Something like that, because, okay, I was old enough to know that I needed to start immediately training professionally up from the 2,000 kilometers I had [ridden] in my life. I was just sending emails around, actually asking simply, ‘Yeah. What do I need to do or be so that I can join your team or try to be a professional? What does it take?’”

This was in 2012. He got a few responses and a meeting with Andrej Hauptman, now with UAE-Emirates who was then working at Adria Mobil, Slovenia’s prime continental-level team. “They were, like, ‘Wow, what did you do before?’” Roglič says. “And they were thinking, hopefully [I] was like some Nordic skier or runner or whatever. But then I say, ski jumping, and they were like, ‘Oof, whoa, uh, okay, let’s, uh, let’s see.’”

Encouraged, he spent 3,000 euros on a bike and basic equipment, enrolled in some training programs, including one with Marko Polanc (father of the Slovenian pro Jan Polanc), a sports director at Rog Radenska, another of Slovenia’s continental teams. When Roglič talks about this period in his life, his voice gets blustery as he describes a rough learning process during which he was submerged into cycling like someone pushed off a diving board and told to learn how to swim. “I started really late. I didn’t know how to put clothes on and off, how to eat, how to drink,” he says, his eyebrows knitted. “I needed to practice everything. You know, also taking a piss from the bike. I needed to learn really, really fast. And honestly, it’s painful because yes, you hit the ground a lot of times in the feeding zone and this and that.” He pauses as if realizing how depressing this sounds.

“But when you want to keep going, you’ll always come through.”

Stage 4 of the Giro d’Italia plays in Spanish on the television in his hotel room at the team camp in southern Spain. As we speak, his eyes glance up occasionally to check in on his teammates, who at the moment are enduring a rather unsavory day of mountains and bad weather.

“Today, you know, watching the Giro, there is really going on a lot of things, hm? The climb at the end is just, really, really the final part,” he muses.

“Yeah, it’s brutal,” I agree. “I’m in the U.S., so to watch the Giro every morning, I have to wake up at 5. This is the first time I’m writing about a whole grand tour. It’s, like, wild.”

“It’s busy, huh? For us, it’s easier.” He chuckles. “The only thing I have to do is just pedal every day.”

The joke feels like a validation, and it’s a convenient segue.

“So, what was your first Grand Tour like?” I ask.

Still laughing, he rubs his forehead as though reliving the exhaustion.

“Super super hard for me. It was the Giro, actually—I did it in 2016 and, like, two times I almost went home. I was sprinting for the time limits to still be in the race. I mean, whoa, it was just super hard.” He pauses for a moment, then immediately follows this story of epic suffering with a casual, “Still, I got some good results, I won a stage.” I have to stop myself from cracking up when he continues, “But yeah, I also suffered really, really a lot, huh?”

I check my watch. We only have a few minutes left, and I ask if he’s got any more good stories he feels like telling.

“I’m not good with the stories. I want to be more the guy with the facts,” he tells me before launching into yet another tale about suffering, this time during his first stage race.

“[It] was Coppi e Bartali, and after two days I couldn’t walk on the stairs anymore. I couldn’t imagine how they do it for three weeks. And then suddenly, I was there and again, it was a discovery for me—because I was not from the sport—that you do so much physically, you’re suffering so much.” He pauses to glance up at the TV once more. “It’s something new, huh?” he ponders as he watches the drama unfold. “Something new to push and really see how far you can go.”

When Roglič first started riding for Adria Mobil in 2013, he was already 23. Considering that most riders in the modern peloton, like Chris Froome or Roglič’s fellow Slovenian Tadej Pogačar, start training and racing around age 12 or 13 and likely will retire in their mid-30s, that’s a lot of ground to make up. The most notable achievement of Roglič’s first year was a 15th place in the general classification at the 2013 Tour of Slovenia.

The next year, he won his first bike races: Stage 2 of the Tour d’Azerbaïdjan and the minor one-day race, Croatia-Slovenia. Just a year later, in 2015, he won both a stage and the general classification in the Tour of Slovenia and the Tour d’Azerbaïdjan. WorldTour teams began to notice. Frans Maasen, a sports director at Lotto-NL Jumbo (now Jumbo-Visma) told VeloNews: “We flew him to the Netherlands to take a test. He was like a Ferrari.”

The following year, Roglič joined the Dutch team as a domestique. He quickly produced notable results, specifically in the time trial, where it became apparent that Roglič was particularly gifted after winning Stage 9 of the Giro d’Italia, his first Grand Tour stage win, and the Slovenian National Time Trial Championships. After that, his rise to fame can only be described as meteoric. In 2017, he won his first WorldTour stage race, the Volta ao Algarve in Portugal, a stage of the Tour de France, and took silver in the time trial World Championships. In 2018, he won Itzulia Basque Country, Tour de Romandie, and the Tour of Slovenia all in succession, capping things off with an astonishing fourth place in the Tour de France.

Then, in 2019, just six years after he first learned how to race a bicycle, Primož Roglič would win his first Grand Tour, the Vuelta a España. This is a feat so incredible, it’s worth reiterating even though Roglič’s talent has become such a consistent, looming presence in the current peloton. It’s worth reiterating because this man used to be nobody—a failed ski jumper, a college dropout, a janitor, a dreamer.

And for Roglič, that’s what cycling is, and remains: a dream. That’s despite all his successes and all the suffering required to achieve them. The “guy with the facts” is more a starry-eyed idealist than anything else, speaking of lofty aspirations and the rewards of hard work with something almost like naivete.

Underneath that withdrawn public persona, there is a different person, just like Roglič’s teammates and family have said. And I can say, with all my journalistic integrity, passed through the scrutiny of fact checkers, that I have met that person. That person is compassionate, warm and genial, an attentive listener with a dry sense of humor. Deep down, that person frets about being a good role model for young people. He wants to be remembered not only for his victories but for, in his words, “the fight that I gave every time.” He’s sentimental about fatherhood (his son, Lev, was born in 2019), describing it as beautiful, despite the lack of sleep he gets at home.

He’s not a history junkie, not one for old-school peloton customs or unwritten rules, which sometimes draws criticism from his fellow riders. His comrades didn’t take kindly to the moment, in Stage 7 of this year’s Paris-Nice, when Roglič, fist in the air, pipped Gino Mäder at the line after the young Swiss rider had been in the breakaway all day and was set to get his first-ever WorldTour win. When Roglič crashed and tried to bridge back to the peloton the next day, no one was particularly keen to wait up for him.

In fact, Roglič admits that he knew nothing about cycling until he took it up himself, so he has no idealized concept of the sport that might be prone to disillusion, no passion left over from childhood to be deflated by the dull reality of life in the professional peloton. And he’s not one to talk about the future, though obviously the Tour de France is looming, and after his shocking defeat last year, there’s no doubt he’s on a quest for redemption.

Beyond that he doesn’t like to make predictions, which in a sport like cycling feel like promises one can’t possibly keep. We know based on last year that Roglič has the potential to win the Tour, we know that he has the resolve and drive to do so, we know that we will be watching him with the hope that he will finally have his day in the sun. All of this, however, is up to him, to his teammates, to his training, to luck. But that is tomorrow. Today he’s watching the Giro d’Italia in a cramped hotel room in Spain, talking to me over Zoom.

Near the end of the video call, I feel a need to confess to him my own dilemma, wherein I’ve become unsatisfied with my career. I do not ask myself about the journalistic ethics of confessing about one’s own life to an interviewee, because from the beginning of this whole endeavor, I believed (with no rationality whatsoever) that our first conversation would be the only time that he and I would ever speak. But why believe things like this, I wonder. If Roglič did things like that, he’d have no reason to ride the Tour de France again. In the end, I see the confession as a kind of insurance against my own failure. Even if I fail at writing this profile, fail to prove myself as a cycling journalist, at least I would have this moment of connection with someone I deeply respect—someone whose story I turn to in my own periods of insecurity and fear and sadness.

I do not realize in the moment that I am, in fact, in the middle of redeeming myself from the disappointment of that first interview, that I have gotten all I needed, that I will in fact prevail, and that I am doing so by taking risks, by being open and honest and totally myself, even though that is perhaps the most difficult thing one can be in the presence of a stranger one admires so very much.

“Can I tell you something before we go?” I ask.

“Tell me,” he says, propping his chin on the hand not holding his phone.

“I only started writing about cycling in September of last year after the Tour because of what happened there,” I admit. “My first essay that I published in a magazine was about you. So I kind of owe you one, because right now I’m in this process of changing careers. I write mostly about architecture and design, but I started to get tired of it. Once I discovered writing about cycling, I was like, ‘Whoa, this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.’ I guess I’m kind of in the process of quitting ski jumping of my own right now.”

He chuckles.

“So, yeah,” I finish, exhaling deeply. “I just want to say, this was really important to me and really special. Thank you so much.”

Roglič, perhaps realizing the vulnerability of the situation, offers a smile. “Wow, no, thank you. I’m just really, really glad we can share things like this,” he says, his voice warm and sincere. “And, yeah, I would be really happy if I could say, Oh, yeah, it will be really fun and nice, but yeah, you have to expect this fucking hard sport, huh?”

I laugh, because I know he’s right, because he is being genuine and honest, because he is also laughing.

He finishes with some simple words of encouragement.

“Just stay safe and enjoy it.”

“Thank you,” I say.

“Thank you, huh?” he replies. “Take care and we keep in touch, yeah?”

I nod furiously, and just like that, it’s over. I rip out my headphones, exhale deeply, and put the race back on, but I can’t focus on anything other than what has just transpired. I look around as if searching for something to lock onto for stability. I find it on the wall.

On my bulletin board, hastily scrawled on the back of a CVS receipt from February, is an email address and phone number. I remove the thumbtack and hold the waxy paper in my hand, the sound of Joe Dombrowski winning the fourth stage of the Giro d’Italia filling the room from my tinny MacBook speakers.

It’s one of those moments where time feels shrunken and heavy, like you’re watching your life from the perspective of someone else. It finally occurs to me that this could not have gone more perfectly, that no matter what happens after, there will be an after. I have not failed. I have seen what I wanted to see. I have searched for this person, and I have found him.

The rest of the answers, answers to those existential questions of what one wants to be in this world, those will come later. For now, I remember what Roglič said to me way back in February. It’s sandwiched between an ‘uhh, yeah’ and the rather dark story about finishing his early races without food or drink out of fear of crashing, crossing the line hypoglycemic. I roll it over in my mind, repeating it, matching the motion with my thumb against the receipt.

At the end, maybe we both figure it out.

Kate Wagner used to be many things—a classical musician, a sound engineer, a broke grad student studying concert halls from the ’70s. Originally known as an architecture and cultural critic, her work in cycling journalism can be found in Bicycling, CyclingNews, ProCycling. This year, she is manifesting her dream of covering all three weeks of the Tour de France in person. Follow her updates in her newsletter derailleur.

Kate Wagner is a cycling journalist whose work can be found in Bicycling, CyclingNews, ProCycling, and in her newsletter derailleur.