If you prefer your opinions on cycling equipment to go unchallenged, and if you like the idea that there are easy answers and that all products fall neatly in line with the stereotypes you hear from the mouth of an embittered shop mechanic, then don’t become a tech editor at a cycling magazine.

When I started way back when, I thought I knew everything. I was a mechanic and service manager in a bike shop, and I voraciously read all the magazines. I knew steel was real, titanium was magical, carbon was brittle, and aluminum was harsh. Everything about bikes was so tidy and clear.

Then I began to ride more bikes—a lot of bikes—and I learned that I knew nothing. I discovered that a lot of what passes for common knowledge in bike shops, on group rides, at the trailheads, and eventually in online discussions has, at best, a sliver of truth wrapped in a whole lot of crap.

I get it—people like it when things are black or white. But cycling equipment isn’t like that: I’m more surprised to be proven right than to be shown I’m wrong. For a good 10 years or so of my career, this frustrated me. Now I enjoy the learning journey. Even though I’ll never know all there is to know about bikes, I delight in how much they continually surprise me.

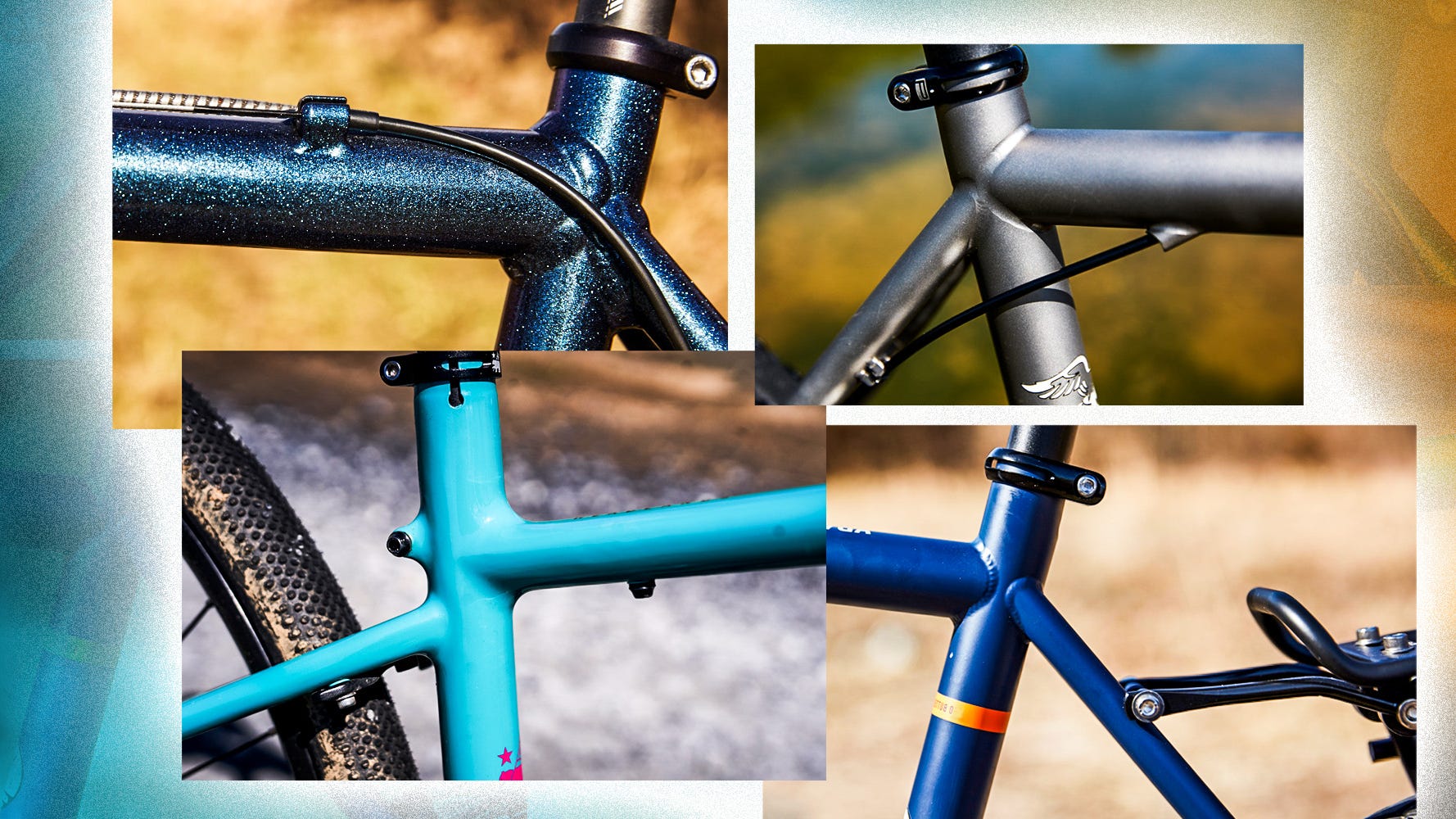

Almost every cycling publication has a story explaining frame materials—here’s ours—because many cyclists want to know this information. Frame material certainly plays some role in a bike’s overall character, but it’s far from the only thing that contributes to its feel and performance. So when you hear that aluminum leads to stiff and harsh riding, while steel and titanium make for a smoother experience, the truth is a lot more nuanced than that.

Let me tell you about the three most memorably harsh, dead, uncomfortable, and just downright shitty riding road bikes I’ve ridden: one was carbon fiber, one was titanium, and one was steel. All were high-end bikes. (I’m withholding the names because all three are no longer in production and the steel builder is out of business). The one frame material that I’ve never had a bad ride experience from: aluminum.

You know that whole aluminum-is-stiff thing? Well, here’s how modulus of elasticity of the three metals rank in gigapascals (GPa): Steel comes in around 200GPa, titanium is around 100GPa, and aluminum is about 70GPa. That means steel is almost three times as stiff as aluminum. Are there stiff aluminum frames? Yes, but anyone who thinks aluminum always results in a stiff frame needs to familiarize themselves with the famously noodly Alan frames of the past.

But stiffness is only one property. When you build a frame, you need to also consider density, strength, durability/toughness, elongation, and things like cost and ease of working with the material. A material can have amazing properties on paper, but if it can’t economically be turned into a frame with consistent performance and durability, those amazing properties are meaningless. A good builder can make any material ride brilliantly—just like any material can be ruined by improper execution.

Once you have a frame, then you put parts on it. And those parts have their own qualities. When you ride a bike, you’re not just feeling the frame material—you’re feeling the frame and all the other parts hung on it. You’re feeling the flex of the wheels, the tire pressure, the vibration absorption of the bar tape, the stiffness of your shoe soles, and the tightness of your QRs/thru axles. I have a super stout Zipp SL Speed stem that I know not to put on an already stiff bike because it’ll push the bike over the edge and make it feel harsh. Yet this same stem can improve the feel of the front end of a bike that I find slightly too soft.

Your weight is also a factor. I recall one carbon test bike that lightweight riders hated because it was harsh, and heavier riders loved because it rode so smoothly. Height is a factor, too. Bigger frames for taller riders behave differently than smaller frames for shorter riders: That’s the revelation behind Specialized’s Rider First Engineering concept. Change your fit from an upright to a low position that puts more weight on your hands, and a bike will feel and handle differently.

What also frustrates me about these materials stories is that they make it seem like there’s more choice than there is. Like you could walk into a shop and find $1,000 Shimano Claris-equipped bikes built of titanium, carbon, steel, and aluminum. That’s obviously not true. From about $600 to $2,000, almost all bikes are aluminum. When you exceed $2,000, you begin to get some carbon-fiber options, though a $2,000 carbon bike and a $2,000 aluminum bike are differently equipped in ways that make direct comparison of materials alone difficult.

Once you’re above $3,500 or so, most frames become carbon. It’s only really when you’re looking at high-end and boutique stuff that you really have the choice of otherwise-equal bikes made from the four materials. And even then, it’s not so much about the material itself as the builder and their philosophy. Do you buy a Richard Sachs because it’s steel, or because it’s made by Richard Sachs? I believe a Sachs would still be a Sachs if he used titanium. Or aluminum. Or carbon.

How a bike rides is much, much more than frame material. I will say I’ve found some subtleties that are almost always present in the various materials; they’re primarily nuances in what frequencies that a frame damps out or passes along. Aluminum feels a bit quieter, steel buzzes the most, and titanium is somewhere between the two. But even so, I no longer look at a frame’s material and make any assumptions on how it might ride. Experience beat those presumptions out of me. Any material can ride well; any material can ride poorly. Design, execution, and details matter more than material.

A gear editor for his entire career, Matt’s journey to becoming a leading cycling tech journalist started in 1995, and he’s been at it ever since; likely riding more cycling equipment than anyone on the planet along the way. Previous to his time with Bicycling, Matt worked in bike shops as a service manager, mechanic, and sales person. Based in Durango, Colorado, he enjoys riding and testing any and all kinds of bikes, so you’re just as likely to see him on a road bike dressed in Lycra at a Tuesday night worlds ride as you are to find him dressed in a full face helmet and pads riding a bike park on an enduro bike. He doesn’t race often, but he’s game for anything; having entered road races, criteriums, trials competitions, dual slalom, downhill races, enduros, stage races, short track, time trials, and gran fondos. Next up on his to-do list: a multi day bikepacking trip, and an e-bike race.