You might compare professional cycling in Europe today to Hollywood movies of the 1930s and 1940s. Both worlds have heaped superstar status on their leading actors. Both worlds are (or were) dominated by whiteness. Yes, the odd Black actor did appear in some of those old movies—albeit as the mammy, the butler, or the chauffeur. Likewise, the Tour de France and the Tour de Feminin have seen appearances by Black riders over the past 10 years or so. But when you consider present-day Hollywood, the similarity ends: Total whiteness of actors in leading movie roles has shifted, and more Black actors are now headlining Hollywood films. By contrast, Black representation in European professional cycling remains stuck in a 1930s Hollywood time warp.

Whether you agree with my Old Hollywood analogy or not, the facts of the two white-dominated worlds remain: The stories of generation after generation of Black Americans and Europeans are framed by the poisonous racism rooted in transatlantic slavery. Black people in the Western world live under the spell of a persistent Eurocentric narrative and vision. The world of professional cycling is no exception.

I am a Black British man. I raced my bike for 20 years, from 1994 to 2014. I still ride the bike. But it was the London 2012 Summer Olympics, and particularly the euphoric celebrations of Great Britain’s gold-medal-winning cycling success in what I describe as “the velodrome of whiteness,” that I began to ask myself: What about Black British cyclists? Why in my lifetime haven’t I ever seen a Black British road or track cyclist representing Great Britain on the track or on the road at the Olympic Games?

More From Bicycling

The same questions could be asked in the United States. The track sprint sensation Nelson Vails comes to my memory for the fact that he was an African American cyclist winning at home in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. But that was close to 40 years ago. Before Vails, the Black cycling superstar was Major Taylor. His feats are more than 100 years in the past; yet today, the same black-and-white photos of Taylor continue to pop up in reverential social media tributes. Taylor was phenomenal, and his story should be told and remembered. But this should not be the only narrative to represent Black desire and excellence in cycling.

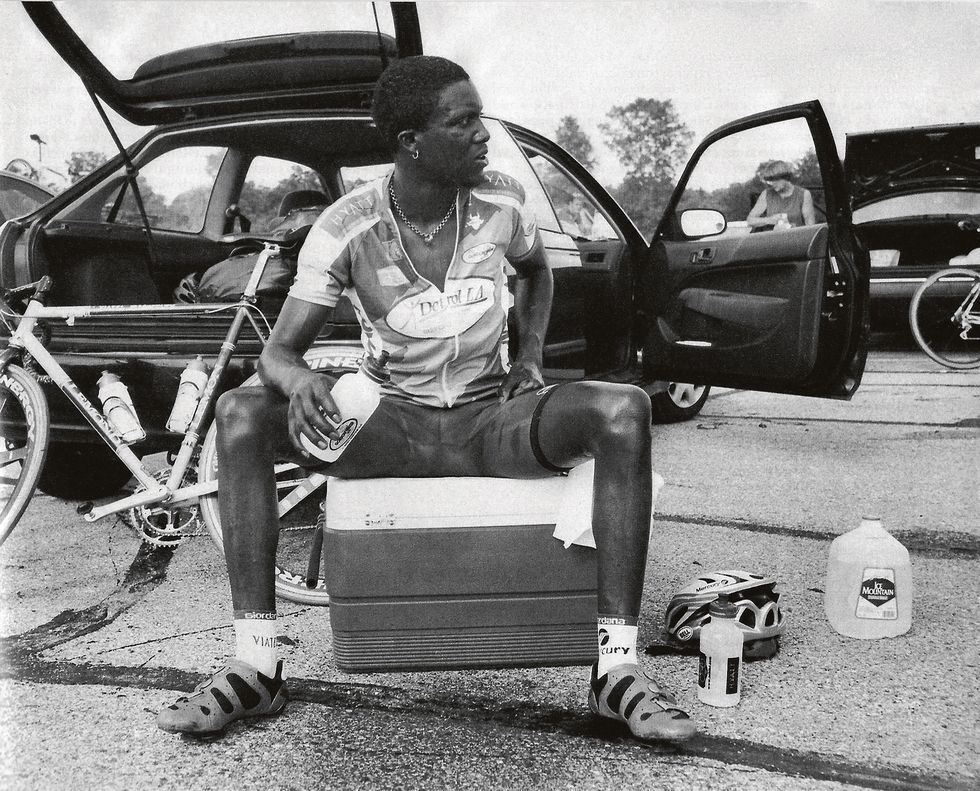

If you are African American, at least there is an icon or two in the sport of cycling as reference points. Today, the Williams brothers, Justin and Cory of L39ion, are shifting people’s focus to a new narrative of Black excellence in professional cycling. However, if you are a Black British cycling athlete looking to find a mirror of inspiration from the past, there is no one obvious. On the other hand, young white cyclists who are looking into the mirror of inspiration as a reference point have a full chronology of representative champions in the sport.

It was only toward the end of my competitive racing days that I became aware of Black British road and track racers, people such as Maurice Burton, Russell Williams, David Clarke, Mark McKay, and Christian Lyte. But I didn’t know their stories. How did they get into the sport? Who were their mentors? What were the clubs they joined? What were their breakthrough races? How did they become cycling champions? What was their relationship with the national bodies? Why did I not see them racing at the World Championships, the Commonwealth Games, or the Olympics?

Join Bicycling All Access for more great cycling stories

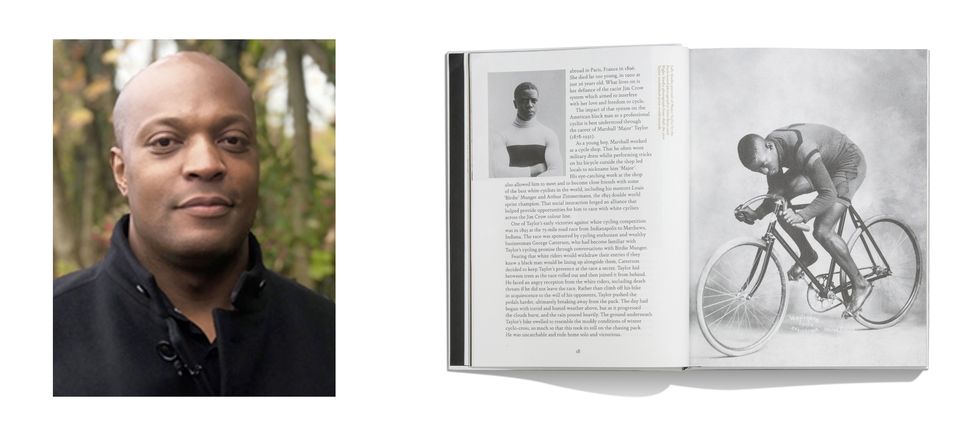

Around 2016 I began looking into their lives. I collected photographs, memorabilia, and their oral testimonies for what became my 2018 exhibition at the University of Brighton, titled “Made in Britain: Uncovering the Life Histories of Black British Champions in Cycling.” I wanted the exhibition (which was shown again at the 2019 UCI Road Championships in Yorkshire) to engage the public in anti-racist discourse to challenge whiteness in cycling. My ultimate goal was to publish these stories in a book that raised the profiles of exceptional Black athletes and their lives in the sport.

I see my work as Black Lives Matter work that began before 2020, before the anti-racism protests known to the world as the Black Lives Matter movement gained global attention. During that year, I watched how worldwide protests instigated a frenzied media interest and inquiry into the experiences of Black people. I watched how this filtered into the world of cycling. Suddenly, the cycling media began to enter the field I was working in. Here they were, with their excavation equipment for digging up the stories of forgotten Black racing cyclists.

Post-2020, Black Lives Matter anti-racism action has waned, along with media interest in Black cyclists’ lives and experiences. The field has emptied. One or two writers remain, but most have returned to their business-as-usual focus on the Grand Tours and the Classics.

My interest in making meaning of the Black experience in cycling continues. This has extended into an international exploration and historical comparison of experiences. I wanted to get deeper meaning about my own experiences as a Black British cyclist and racer. I wanted to test the truth I held in my thoughts about the sport. I saw that the best approach for me would be to place myself among Black elite cyclists who had lived before me and those who were current.

My book Desire, Discrimination, Determination: Black Champions in Cycling emerged from the foundations of my research and expands on my exhibition work. It shares international, historical, and contemporary accounts of Black people’s experiences in grassroots cycling and elite competitive racing in the white world of the sport. I share the lives and voices of Black cyclists through a history of cross-cultural and cross-ethnic encounters in the U.K., U.S., France, South Africa, and Caribbean nations. I examine cycling segregation between Black and white people in the U.S. during Jim Crow days, and in comparison, to Black and white cyclists during apartheid in South Africa. I share accounts from Black racing cyclists across different generations and different countries, from Major Taylor to Justin Williams; Maurice Burton to Rahsaan Bahati; Germain Ibron to Grégory Baugé; Kittie Knox to Marie-Divine Taky Kouamé.

Nothing I learned about the racial violence and the stymied career opportunities faced by cyclists over the generations has shocked me. From being bullied off the road in professional road racing to being called “monkeys,” Black cyclists are aware that the racist past remains in the present. Throughout the book, a powerful voice comes from the exceptional British rider Maurice Burton, a pro track racer who competed at the 1974 Commonwealth Games. Burton never fails to give a vivid account of the good, the bad, and the ugliness of what he had to contend with while he was racing in the U.K. and as a Six Day track racer in Europe. Here he reflects on winning his first senior British championship in 1974:

“At the medal ceremony when I was holding the flowers, some people in the crowd were booing. It wasn’t something that surprised me. It was because of the colour of my skin.”

And in leaving England and racing in mainland Europe, Burton could not escape the attention given to his blackness in the white-dominated space. He describes his experience when he traveled to Vienna and lined up against Six Day legend Patrick Sercu:

“When I arrived, I saw the newspaper, and one of the sports page headlines read: ‘Can the N***** Beat Sercu?’ Now can you imagine what sort of people were going to be in that crowd? The velodrome was owned by a former SS officer who was the father of an Austrian rider.”

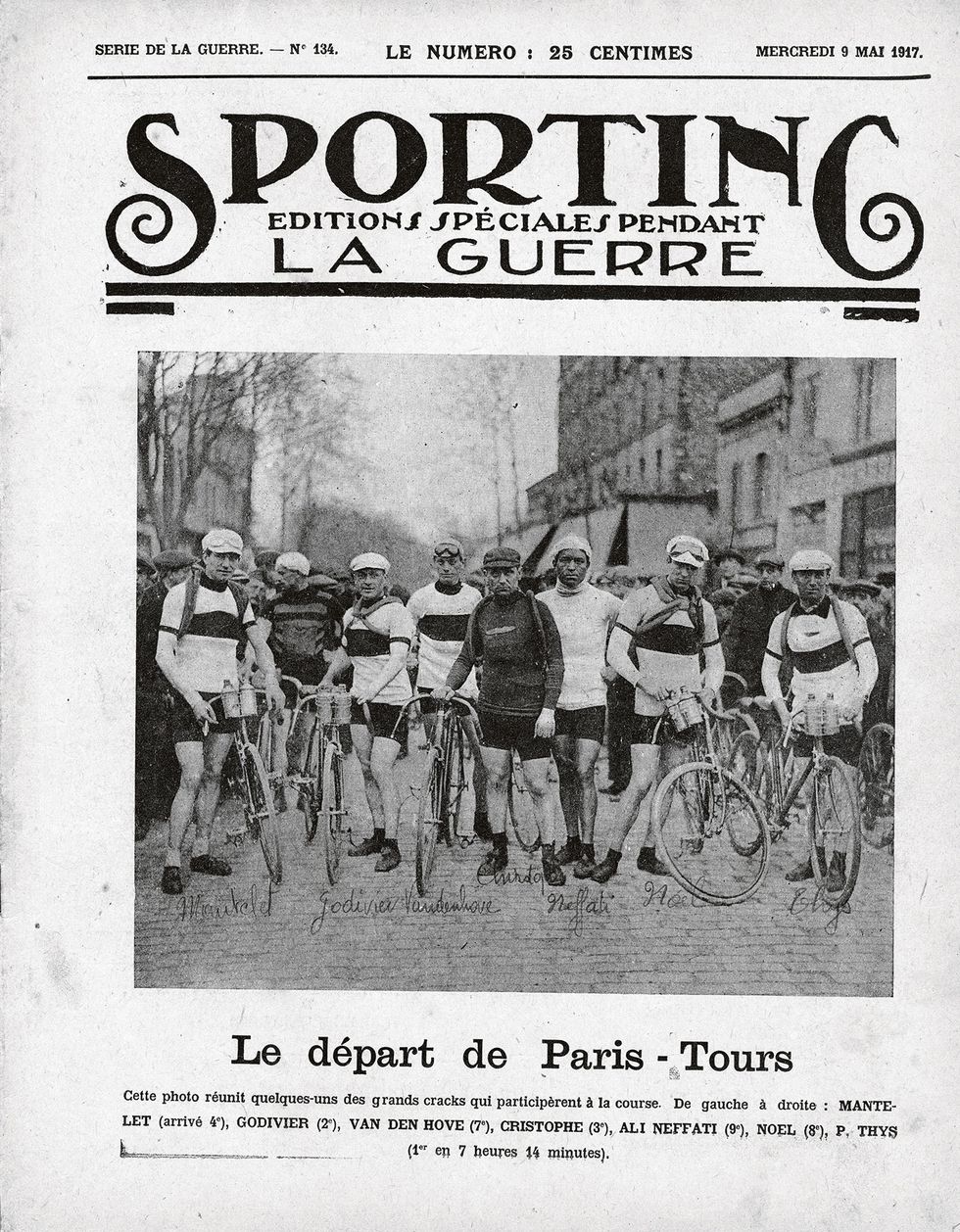

This racism is also maintained by a narcissistic, sentimental kind of history. It is culturally reproduced and perpetuated by cheerleading in cycling media, often in reference to past Grand Tour and Classics winners who have played their roles reproducing the narratives. Merckx, Simpson, Hinault, and Coppi are examples of the superstar professional cyclists from the past who are reflected in the faces of those in the present, such as Alaphilippe, Van Aert, Wiggins, and Ganna. Not one of these is a Black athlete. Black people in cycling peer into this world. Some dream of being there one day, on the stage. Can we imagine days ahead in the sport where a dominant team of Black cyclists with a Black leader becomes a force in the Grand Tours and Classics?

If the powers in cycling genuinely want to extricate the sport from its white, Eurocentric traditions akin to 1930s Hollywood, they will need to embrace an inclusive revolution of creative thinking and action. This will take acceptance, effort, and long-term financial and resource investment in Black cycling athletes, Black cycling countries, and Black cycling leadership. The focus needs to be on advancing toward a better place for the sport, and away from the exclusive narrow norms of the white cycling narrative.

There are very few books about grassroots and competitive cycling written about Black people, let alone written by a Black person. Desire, Discrimination, Determination: Black Champions in Cycling offers a new paradigm for knowing cycling, a new way of seeing the sport of cycling through the histories and lenses of Black people. This book follows the last one written by a Black man, Major Taylor’s autobiographical work, more than 100 years ago. This gap of Black-penned knowledge and understanding for giving voice and a platform to Black people in cycling has now been bridged.

Dr. Marlon Lee Moncrieffe is the author of Desire, Discrimination, Determination: Black Champions in Cycling. He researches international education, anti-racism, and Black British culture at the University of Brighton.