With the availability of new bikes still pinched by the ongoing pandemic, many riders are making a used bike their next bike. There are a lot of great used bikes out there looking for a new home, and with the Pro’s Closet changing the used bike market forever with its solid pre-sale inspection and service (plus its excellent post-sale guarantees), there’s never been a better time to buy a used bike.

While the past few generations of bikes are some of the best ever, there are still a few wonky “standards” and dead-end technologies you’ll want to avoid when shopping for your next bike. The thought behind the seven items below is since a used bike is already older and has some miles on it, that means service is likely to happen sooner than a brand-new bike. The older the parts, and the more obscure, the tech and standards are, the harder it is to find replacement parts, or the information and tools for required for servicing those parts. Will your mechanic know how to service the funky Formula disc brakes/Campagnolo EPS shifting system on that sweet Colnago C59 Disc you picked up? Perhaps, but not likely. Plus, even if they do, can they get the parts they need? It’s a lot less likely than if the bike has Shimano Dura-Ace Di2.

Below are seven things to avoid when shopping for a new (used) bike. Did I miss anything? Let me know in the comments.

More From Bicycling

Press Fit Bottom Brackets

While some riders and mechanics believe that any press-fit bottom bracket is the work of the devil, in my opinion, press-fit BBs are a very nuanced topic.

Here’s the thing: modern carbon frames—stiff, with large diameter tubes—are loud and amplify noises. A crank (with spider and chainrings) and the bottom bracket are a series of connected parts exposed to the environment (dirt and water). It doesn’t matter what’s going on down there at the bottom bracket; everything eventually makes noise. I’ve had plenty of bikes with threaded BBs make noise—some when brand new—just as I’ve had some bikes with press-fit bottom brackets stay silent even after 100s of hours and 1000’s of miles of riding.

Also, let me point this out: the bike may take a threaded BB, but in most cases, a modern threaded BB is just a set of bearings press fit into cups. So, though the new Specialized Tarmac SL7 has a threaded BB shell, even if you put in a Shimano or even Chris King bottom bracket, you’re still riding it with press-fit bearings. The reality is, a properly designed and manufactured press-fit interface is a very efficient system widely used elsewhere on a bike—and in all sorts of other equipment—with few issues.

However: all bottom brackets need service and replacement on a semi-regular basis, and this is where threaded systems have an advantage. It is (generally) easier and faster—and there are fewer potential headaches—to “service” a threaded system than a press-fit system. Service in scare quotes because the only service you can do to many bottom brackets is throw the old one in the trash and install a new one.

Still, a BSA threaded BB is the most standard of all bicycle standards—there are approximately 1,482,685 other BB standards—so there are plenty of options for replacements and upgrades. Plus, a BSA threaded BB shell can accommodate most crank axle systems, granting you the flexibility for future upgrades.

Proprietary Suspension Bits

I’ll probably forget a few, but take a pass on the following proprietary suspension bits: Cannondale Lefty forks, Cannondale DYAD, Cannondale Gemini, Trek Thru Shaft, Trek IsoStrut, Scott Twinloc, and the Specialized BRAIN. I’ll add BMC’s Race Application Dropper and Canyon’s Shapeshifter too.

I’m somewhat conflicted about saying this, because I applaud brands for trying new things in the name of improved performance and rider experience. In many of the cases above, there is a real benefit to the technology for the bike’s intended use. But, things get complicated when it’s time to service the parts—you should service your suspension AT LEAST annually—or you need replacement parts. With proprietary suspension bits, you’re potentially looking at longer repair times and harder-to-find parts, which means more expensive repairs. As a result, your bike might be out of service for a more extended period than if it used standard bits. Then, several years down the road, repairs, and replacement of these special bits becomes more difficult or nearly impossible.

Quick Releases and Disc Brakes

One of my colleagues believes that we will one day look back at open dropouts and quick releases, and shake our heads at how long we clung to such a sketchy and stupid system for keeping wheels in our bikes. I think there’s some truth there, though I still trust and ride the system on my rim-brake-equipped road bikes.

When it comes to disc brake-equipped bikes, quickly walk away from any bike with discs and quick releases and open dropouts. This wheel retention system isn’t secure enough, stiff enough, nor consistently aligns properly for use with disc brakes. Disc brakes = thru-axles—no exceptions.

Integrated Seat Posts/Masts

ISP’s look really sleek, and in some cases, they save weight and improve a bike’s seated compliance. However, once cut, there’s no going back. And once cut, they offer limited adjustment. So, if you’re considering a used bike with a seat mast, you need to be sure the bike either has a mast that’s longer than what you need or happens to be cut precisely for your saddle height (with your specific saddle, crank length, and pedal combo considered). But once it’s cut for your saddle height, you can’t resell this bike—or let friends or family borrow it—to a person who runs a taller saddle height. Bikes with seat masts are also a pain in the ass to pack into a travel case. Overall, there are no used bikes out there with ISPs that are so damn special that I’d say they’re worth the extra hassle.

I do have two caveats, however.

One, you can convert some ISP systems to work with a regular seat post. So if you’re willing to do the extra legwork needed to figure out if the bike you’re looking at can be converted, and then get the bits needed to make the conversion (and you’re not scared to lop the mast off), you might be able to eliminate the ISP and run a standard seatpost. Personally, I wouldn’t bother as, again, no ISP bike is so special that I’d waste my time on a conversion.

My second caveat is for Trek’s “no-cut” seat mast system used on many Domane, Emonda, and Madone models. As the name describes, there’s no cutting required, plus this system offers plenty of saddle height adjustment. The mast topper is a proprietary Trek part, though, so even though it’s not as annoying as an ISP, it’s not as simple as a standard round post.

Specialized SCS

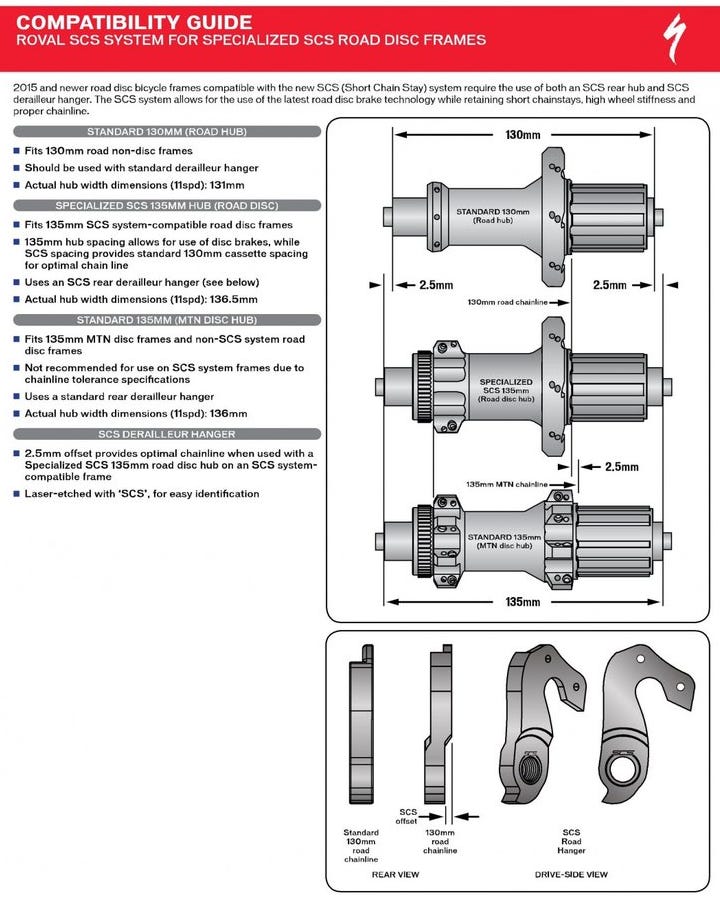

This one results from the chaotic transition from rim brakes and open (QR) dropouts to disc brakes and thru-axles. It was essentially a mashup of 130mm and 135mm spacing, and Specialized had, at the time, good reasons for creating it. I can’t remember what they are anymore—chain line and shifting, I think—and thankfully, Specialized didn’t stick to the *cough* “standard” for long. Avoid it because it’ll make finding a replacement rear wheel/hub—and rear derailleur hanger—a pain in the ass.

Cannondale Ai Offset

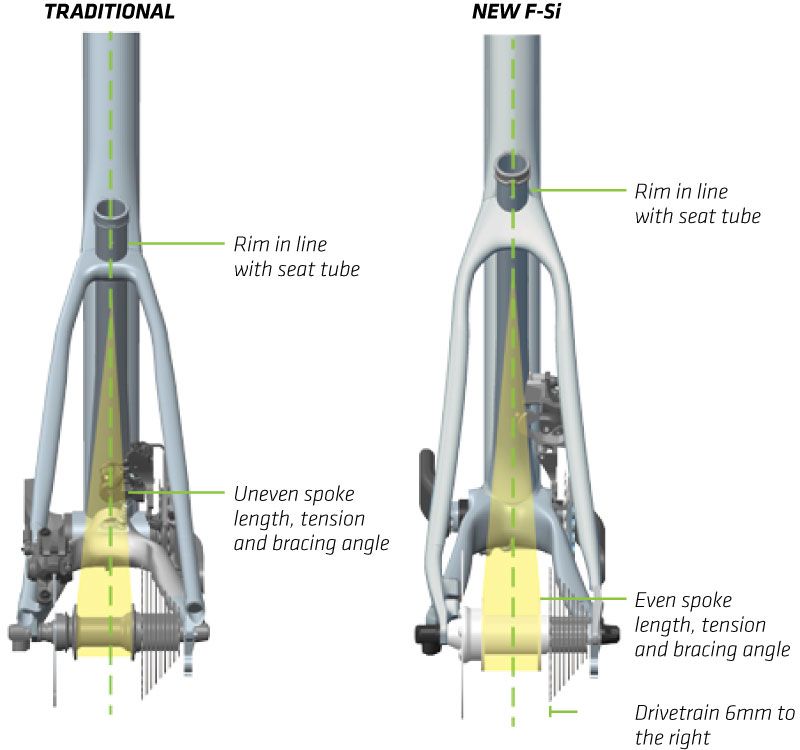

Cannondale’s Ai Offset is a non-standard rear wheel dish (“dish” refers to the centerline of the rim’s position relative to the centerline of the hub). But, like Specialized SCS discussed above, it came about in the hectic overlapping transition from rim to disc, QR to thru-axle, and (for mountain bikes) front derailleur to 1x drivetrains.

Compared to almost every other bike on the planet, an Ai frame shifts the rear triangle away from the centerline of the frame, pushing the hub and drivetrain six millimeters to the right. Unfortunately, that means the rim needs to be shifted six millimeters to the left to center it in the frame. That means you can’t just drop any standard rear wheel in an Ai frame. The saving grace is that a good mechanic can re-dish many wheels to work with Ai offset IF the wheel’s existing spoke lengths allow it. But here’s another case where you’re looking at a whole bunch of hassle, and perhaps spending more money on service, for no significant benefit.

Like SCS, when Cannondale rolled out Ai it made some sense given where bike technology was at the moment. But also like SCS, Ai made sense for about six weeks before new products and better solutions mooted it. Unlike SCS though, Cannondale stuck with Ai offset, and even used it on bikes where it seems to make little sense like the otherwise delightful Habit trail bike.

27.2mm Seatposts

This one is applied explicitly to mountain bikes. However, if you’re shopping for road bikes, a 27.2mm post is a benefit, in my opinion.

I say skip 27.2mm posts when shopping for a mountain bike because it limits your dropper post options. Yes, there are a few 27.2mm droppers out there, but only a few. Plus, due in part to the forces, they’re subjected to, droppers are notoriously unreliable. A larger diameter post is stouter and has more room for robust internals, which helps it be somewhat more reliable than a pinner 27.2mm dropper.

The exception to this advice would be if you’re trying to build the lightest hardtail or XC race bike possible and are okay with sacrificing the extra control a dropper offers. In that case, a lighter, more compliant, 27.2mm post would be a benefit.

A gear editor for his entire career, Matt’s journey to becoming a leading cycling tech journalist started in 1995, and he’s been at it ever since; likely riding more cycling equipment than anyone on the planet along the way. Previous to his time with Bicycling, Matt worked in bike shops as a service manager, mechanic, and sales person. Based in Durango, Colorado, he enjoys riding and testing any and all kinds of bikes, so you’re just as likely to see him on a road bike dressed in Lycra at a Tuesday night worlds ride as you are to find him dressed in a full face helmet and pads riding a bike park on an enduro bike. He doesn’t race often, but he’s game for anything; having entered road races, criteriums, trials competitions, dual slalom, downhill races, enduros, stage races, short track, time trials, and gran fondos. Next up on his to-do list: a multi day bikepacking trip, and an e-bike race.